When I think of him, I think of the kitchen in the home where I lived from the time I was born until I left for college.

My mother still lives there, in our small town in New Jersey. The kitchen is more or less the same, with the original oak cabinets, circa 1960, and the round table that barely seated the six of us. My younger brother’s seat was positioned so close to the oven that he once scalded his back as my mother rushed to serve dinner at 6:00.

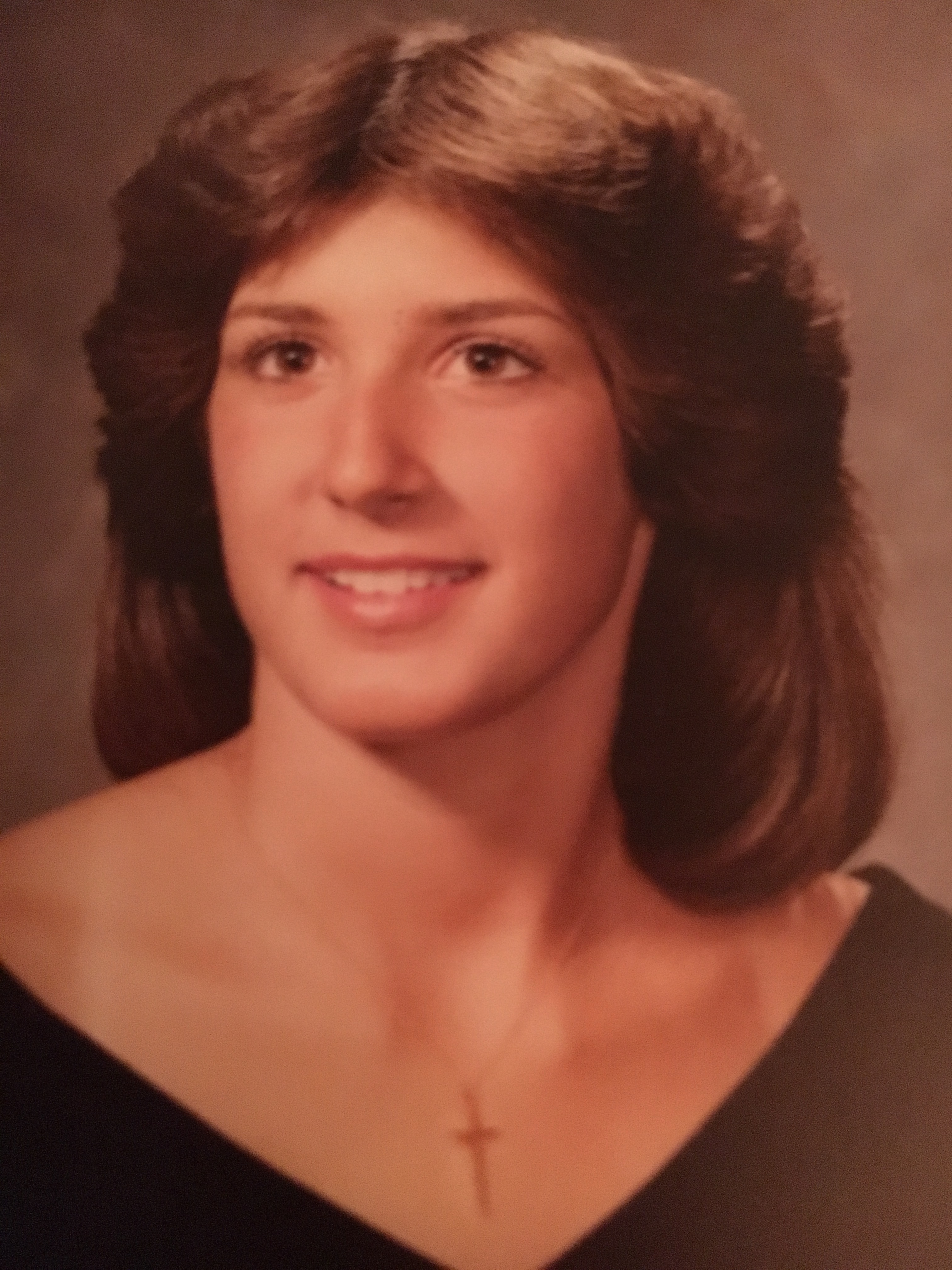

When I picture that table, the memories that come to mind are more or less all the same, like watching a home movie over and over – family dinners filled with lighthearted banter and typical sibling squabbles. Occasionally, I picture the afternoons I spent sitting beside him at that table, once, sometimes twice a week after school, during my junior year of high school. He sipped coffee and we made small talk – about school and my field hockey team. He was a teacher at my Catholic school, and he attended all of the home games. He called me by my nickname, Missy.

As we talked, my mother flitted back and forth from room to room doing chores, cooking dinner, occasionally joining in our conversation. She hovered without seeming to hover but always ended up back in the kitchen – the hub of our house, the nexus of the neighborhood.

Unlike other priests and nuns who visited my parents fairly regularly, it wasn’t entirely clear whether Father Tom came to see my mother or me; we both considered him a friend. I didn’t necessarily look forward to his visits, but I didn't resent them either. I thought of it as killing time in a place with time to kill – a tiny town with few distractions, in the lull before dinner.

Though he looked more like someone from my mother’s generation, with his thinning, prematurely gray hair and small paunch reminiscent of a Franciscan monk, he acted like someone from mine. He reminded me of a young Tim Conway, Carol Burnett’s co-star on TV in the 1970s. He liked to goof around and make silly faces. He must have been about 30 at the time.

I wish I could go back in time and replay one of those afternoons, hear just one conversation, but the words we spoke remain elusive. What is vivid is the stark white clerical collar and the compassionate sound of his voice, always flattering me and making me feel oh-so-special. Lots of adults did back then, especially about my sports achievements. I felt sorry for Father Tom because he was not from our town so we assumed he was a bit lonely; I thought it was sad that he had nobody else to hang out with. He was always gone by the time my father came home for dinner.

After school let out in June, we saw less of him. Then, on an otherwise ordinary summer day, my mother walked into our kitchen and announced that our friend had moved.

“Father Tom was transferred to an Indian reservation in New Mexico,” she said, as shocked as I was to hear the news. I don’t think either of us had any idea why such a personable priest would be banished to such an isolated post. All I knew was that I was disappointed. But not surprised. The diocese sent the Catholic school I attended more than a few teachers that the more urbane, affluent communities didn’t want, and eventually they had been transferred. With Father Tom, we thought we had finally found a winner. He was a favorite in our school, even if theology wasn’t anyone’s favorite subject. Father Tom seemed like a cool uncle which is probably why so many classmates felt a nice connection with him. Even on the topic of religion, he was funny. He somehow managed to preach the word of God while performing what seemed like a stand-up routine with cute quips and antics. He was one of us.

“What?” I asked. “Why didn’t he say goodbye?” I didn’t learn the answer for more than a decade.

I was standing in the kitchen, visiting my parents from my home in New York when my father made a passing reference to Father Tom. In the same breath, he used the phrase “child molester.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked. My mother proceeded to fill me in on the real reason Father Tom was shipped off to the Southwest.

“Father Tom molested two girls in the church rectory,” my mother said, matter-of-factly. As she continued to empty the dishwasher, or stir the pot of gravy, or whatever she was doing to prepare for dinner, I looked up at my parents. Nothing ever happened in our town. Something like this, a scandalous act by a man who sat right in this room, seemed inconceivable.

I reached for a chair, and sat down to try to digest this bombshell. I listened as my mother told me that the girls were sisters, age 13 and 11 when it happened. I knew the older girl.

My first thought was: How is it possible that someone I thought I knew had done something so heinous?

What I asked was: “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“We thought you knew,” my mother said casually, as she continued her chores. I wondered if she thought this was true or if she had decided to protect me from the truth. But now I was 28 years old, for God’s sake. Rather than saying something I might regret, I reverted back to my signature teenage move when I became angry.

Without saying a word, I ran upstairs to the attic. Between a rack of old prom dresses and other dusty, dated clothes and the wedding gifts that didn’t fit in my apartment, was a three-foot square area of pure nostalgia – my high school papers and memorabilia. I rummaged through the boxes until I found what I was looking for – a tri-fold postcard with Native American symbols on the exterior. It was dated October 1981.

I stood in the ill-lighted attic, illuminated by a single bulb hanging 20 feet away, and squinted to make out the words. The envelope was addressed to “Michele (but everyone calls her Missy except her grandmother).” I had smiled the first time I read that salutation, just a few months after he’d left. Father Tom liked to tease me about the fact that nobody called me by my birth name. Now, years later, the teasing took on a different meaning; it felt creepy.

I remembered how he doted on me. Once in awhile, he’d pat my hand in an avuncular manner. At the time, I didn’t realize that his behavior could be interpreted as flirtatious, even coy. Neither, apparently, did my mother, who had to have been equally naïve about his motivations.

I opened the letter and began reading, looking for clues that I may have missed when I first read the letter: “I’d send you my address but I’m leaving his week to work in a remote mountain village and I don’t know where yet. As soon as I do, I’ll let you know because I would like very much to hear from you.” He had written his temporary address and asked me to write back quickly before he left town. He ended by saying, “Be good, Missy, and tell everyone I said ‘hello.’”

Standing in the attic’s afternoon light, reading and rereading these words hurled me back in time, to when the letter arrived. My mother didn’t flinch, probably because she was still unaware of the scandal. By then, I was a few months into my senior year of high school, and Father Tom was the furthest thing from my mind. I read the letter quickly and casually, and stuffed it in my desk drawer along with letters from a few friends who were away at college. I am certain I told my mother about it, and I think I wrote back, but I never heard from him again.

Back then, the letter seemed as innocuous and innocent as those afternoons at the kitchen table. Except now when I looked at it with adult eyes, I feel sullied, as if a peeping (Father) Tom had been spying on me in the shower.

Every word delicately inked in his perfect penmanship was probably planned – as was every afternoon he spent in my kitchen. Yet he never touched me in an inappropriate way. He never spoke to me in a lewd manner.

I looked at the letter and again wondered, If he hadn’t been transferred, would I have been next? I was being groomed by a pedophile. Right in my parents’ kitchen. I just stood there, in the attic, wondering why I had been spared. I needed to let this news sink in before I descended, down to dinner with my family, around that same kitchen table, where I knew the Father Tom tale would be brushed off as a near miss, or a fender bender.

When I process all of this, I also think of my overprotective Italian mother – the original helicopter mom. Father Tom and I were rarely alone for more than a few minutes at a time. Maybe I was spared simply because he never had the opportunity. As a teenager, I’d resented the fact that she and my dad were so omnipresent. In high school, I always had a curfew, and no boys were allowed to enter my bedroom aside from my two brothers. Now, I think of her wearing an invisible cape that protected me.

I walked downstairs and tucked the letter into my suitcase. When I get back home, I place the letter in my bedroom in a fireproof metal box alongside my passport and marriage license. I read the letter every so often, when I learn a new story about a wayward priest or pedophile, and then I stash it back under my bed. I hold onto it because it serves as a reminder that there are many men and women, boys and girls, who weren’t as lucky; and it inspires me to be the kind of mother mine was and still is. Then I take a deep breath and say a little prayer of thanks.

Michele Turk is a writer whose work has appeared in Parents, Parenting, BusinessWeek, USA Weekend, Glamour, Next Avenue, The Washington Post and Brain, Child. She is the author of Blood, Sweat and Tears: An Oral History of the American Red Cross, and she is writing a memoir about parenting a child with Tourette Syndrome. Michele recently took over as president of the Connecticut Press Club. Find her online at www.ablocofwriters.com.