Her arms extended to balance on the steep terrain, Maria Auxiliadora resembles an old-fashioned scale, the kind used to weigh vegetables in the market here, a small town nestled among the fincas, coffee farms of northern Nicaragua. A rosary with plastic beads is looped loosely around her left hand. In her right hand is a stack of warm tortillas tied up in a white handkerchief. With each step, she tips to one side or the other, as if measuring the spiritual weight of the rosary against the earthly burden of the tortillas, heavy with moisture and ash.

The rocky trail is slick from last night’s shower, the air still ripe with moisture. Maria Auxiliadora moves up the incline swiftly, grabbing the muddy path with prehensile toes protected only by flimsy flip-flops. My eyes are fixed on the back of her faded red T-shirt, darkened where blotches of sweat have soaked through and perforated by tiny holes from the barbed-wired fence where she hangs her laundry to dry.

The rosary is a relic of her faith, the tortillas a token offering for the man we will visit today. He is Bernardo Gadea Chavarria, known to everyone in the valley of Chirinaua as simply, Nando. Everyone here has a Nando story. How a dictator’s daughter, who ballooned from the good life in Miami, arrived by helicopter seeking treatment for obesity. How a Mexican movie star, desperate to curb unexplained hair loss, turned to the legendary curandero, healer. How Nando cured a cousin of kidney stones or a friend of warts. We are not alone on the Nando trail. Townspeople tell me that on weekends, upwards of seventy cure-seekers – the lame, the blind, limp children slung across a relative’s shoulder – make the arduous trek to his backwoods clinic each day.

Maria Auxiliadora’s interest in visiting Nando surprises me. In a mostly Catholic town, she is among the most devout. She lights candles at the cathedral each morning and speaks favorably of Padre Douglas, the church’s philandering, over-imbibing, hypochondriac priest. A sign in the window of her home proclaims I AM CATHOLIC to ward off the door-knocking missionaries who troll her barrio, neighborhood, for converts.

Translated to English, Maria Auxiliadora means Mary the Helper. And helpful she is. One of the first people I met when I arrived here two years ago as a Peace Corps volunteer, she showed me around and included me in her family’s celebration of La Purísima, a holiday dedicated to the Virgin Mary. We’ve chatted about Nando a few times, so when she invites me to join her on a hike to visit the unorthodox healer I’ve heard so much about, I eagerly accept.

Maria Auxiliadora ushers me back to the trail. Like most Nicaraguans, her diet consists mainly of gallo pinto, the local staple of red beans and rice, but she is strong and lean. She is also literate, a product of the Sandinistas’ alfabetización campaign which sent Cuban college students into the countryside to educate farmers and their families. She is a librarian by training, and it was through my efforts to establish a children’s library here that I got to know her.

The summer rains have begun, feeding temporary streams that form on slopes eroded by deforestation. As we descend into a deep ravine, we’re serenaded by running water. Sun filters through the canopy and casts a mottled glow on the path. Howler monkeys call out warnings to members of their tribe. We’re nearly two hours into the hike, and I haven’t yet asked Maria Auxiliadora the reason for our visit to Nando. Her malady isn’t apparent, so I assume that her problem is private in nature, an unusual mole in a hidden crease, painful menstrual cycles or depression, often referred to here as “thinking too much.” Though my Spanish is sufficient for shopping, social occasions and the development work I do, I find myself searching for words when it comes to such delicate matters. Finally, I ask.

¿Por qué vamos? Why are we going? Just as I blurt out the question, we’re stopped in our tracks by a whirlwind of flashing lights ahead on the trail. My eyes say police strobe or neon sign, until my brain reminds me that we are hours from the nearest road and far off the electrical grid. Even in town, electricity is fickle, often no more than a few hours each day.

The color is blue. Blue like the glittery, iridescent shades of eyeshadow I coveted in seventh grade: sapphire stardust, cerulean crystal, ocean ice. I remember reading that there are few true blues in nature – sky, water and a handful of flowers and birds – but when they do occur, they are a magnet for the human eye. Bluebirds in spring. Bluebells in an alpine meadow. And on this day, Blue Morpho butterflies in a subtropical forest. Hundreds of them, some with wingspreads of six inches or more. I enter the kaleidoscope, as a gathering of butterflies is aptly called. It’s as if I’ve stepped onto a crowded dance floor, faces and wings flecked by a rotating mirror ball. Butterflies surround me, land on my nose and arms, then, like nightclub patrons, retreat to the margins to drink from a nearby streambed.

Maria Auxiliadora and I linger longer than we should, captivated by a moment that seems part of her plan, a visual hallucinogenic designed to prime my mind for our visit to the famed shaman of the forest. As we hike on, she returns to my question. Es para tí. It’s for you. Suddenly, her intentions become clear. She has lit candles for me and prayed to her beloved Virgin Mary. Nando is the logical next step.

As a childless married woman, just turned 40, the past two years have been a litany of unsolicited advice. Eat pineapple in the afternoon. Eliminate cold beverages. Let your hair grow long. Mostly, I nod graciously, and turn to my textbook for phrases used to politely change the subject in Spanish. In one recent conversation, Maria Auxiliadora refused to relent, and I was frank with her. I hadn’t been, wasn’t, and wouldn’t be pregnant. My infertility is a medically-confirmed, undebatable, irreversible fact. It’s something I’ve known about since late adolescence and come to accept as an adult. Pobrecita. Poor little girl. Maria Auxiliadora’s voice is saturated with pity, but over the years, I’ve trained myself to put a positive spin on my diagnosis. I explain that without children to care for, I’m able to be here, to build libraries, to serve the world in other ways.

But it’s hard to argue with someone who believes in miracles. Maria Auxiliadora reminds me, that like hypnotism and Ouija boards, Nando’s cures are only available to believers. Nando himself is said to have multiple wives, dozens of children and at last count, more than sixty grandchildren. Perhaps living proof, she points out, of a secret fertility formula.

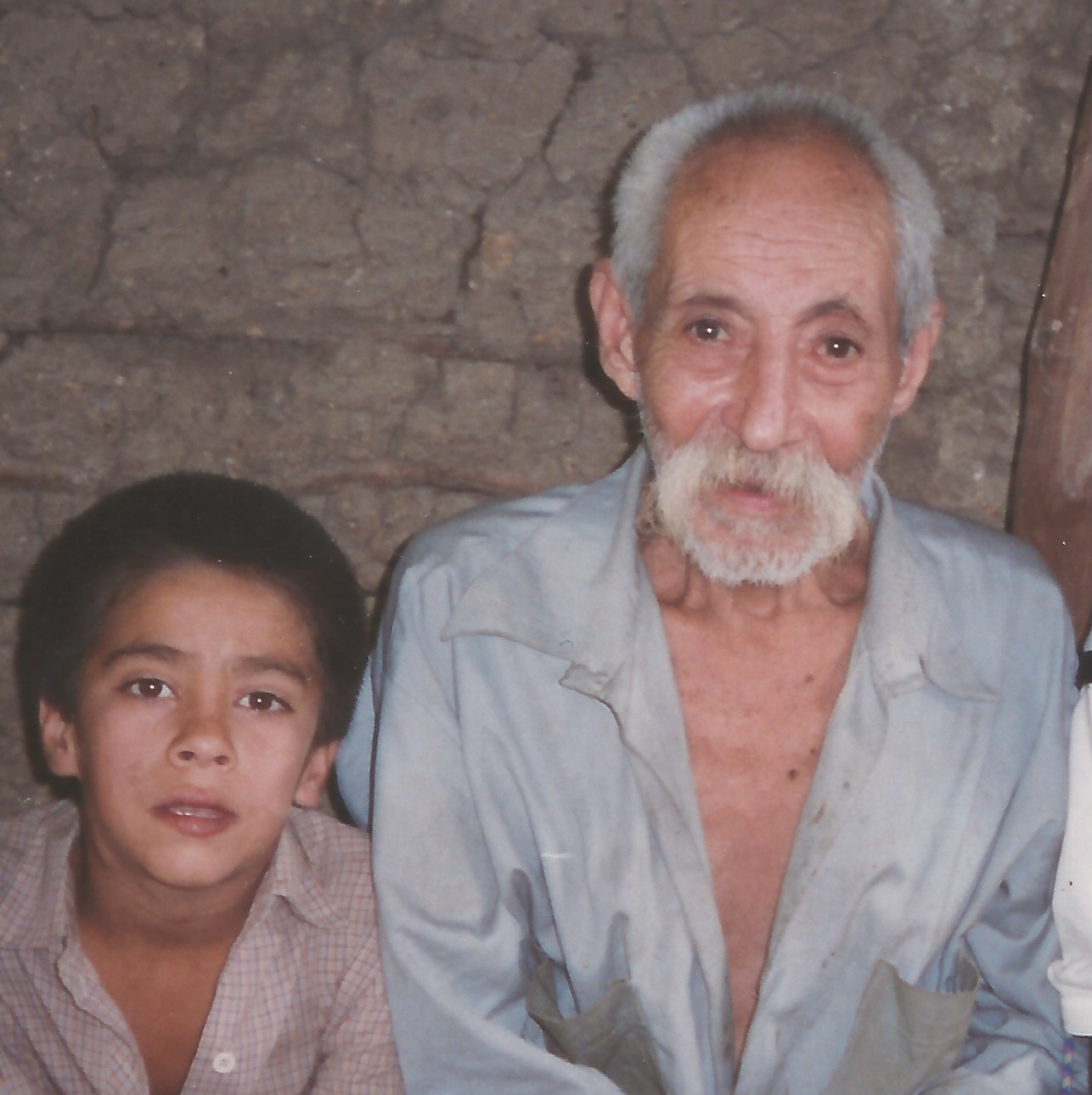

It is misting lightly as we enter Nando’s compound, a collection of run-down, half-finished cement and rebar structures. A welcome party of his progeny come running out to greet us and gratefully take the tortillas. Nando has a worn face with gullies on his forehead like those carved by the rain on the mountainside. His features are dominated by a drooping white mustache that reminds me of the flossy snow we drape on the mantel at Christmas time. He is barefoot, and a grimy blue shirt hangs on his thin frame with its one remaining button. La chela? The white woman? Nando confirms that I’m the patient, using a scrambled form of the word leche, which means milk, and changing the final vowel to -a for the feminine form.

While I offer the standard greetings, Maria Auxiliadora gets right to the point of our visit. Es que ella no tiene hijos. It’s that she doesn’t have children. He nods me toward a rustic wooden bench. One of his adolescent apprentices lights a thick hand-rolled cigar. Nando inhales deeply and exhales a cloud of thick smoke only inches from my face. When I begin to cough, he utters a string of obscenities. I’ve been warned about this, but the next part is a surprise. He spits directly into each ear, making me wonder whether tuberculosis might be spread this way. Then, Nando motions for me to remain seated and disappears into his bodega. A few minutes later he returns with two small packets of chopped-up tree bark, wrapped in large leaves and tied with a thin reed.

I promise Maria Auxiliadora that I will follow Nando’s instructions. Back home, I boil water and steep the shredded bark to make tea. The flavor is not unpleasant, and the tea seems to have a mild sedative effect. I discover that the bark also adds woody overtones to the local rum and cheap Chilean wine that we buy here.

Two weeks later, shortly after dawn, my husband and I are startled by a knock at the door. We’re used to being awakened by roosters, fire crackers and the compulsive sweeping of an elderly neighbor. But this sounds different, urgent. I undo the primitive iron latch and the top half of the door swings open, forming a window. There is a young woman, surely still in her teens, holding a weeks-old baby in a sling. Her facial expression is flat, devoid of emotion other than the resigned stoicism of the country’s most poor and least lucky. I blink the sleep from my eyes. Do I know her? I do not. Her words are few. Te la regalo. I give her to you, as a gift.

This is not the first time someone has offered to give us a child. After all, we live in a country where life is fragile and another mouth to feed can tip a family into despair. There is the keychain-seller in the market who carries a son with withered legs on his shoulders, the two of them so connected that I think of them as a single being. Every time we pass, he lifts the boy up and pretends to hand him over to us. “U.S.A.?” he asks.

Once, on a crowded bus, a mother with a baby in her arms was standing, so I offered my seat. Instead, she handed me the baby to hold on my lap. Farther up the road, the young man sitting behind me tapped me on the shoulder and gestured that the baby’s mother was getting off the bus. I called out to her, and her reply caught me off guard. Es tuya. She’s yours. I shouted to the driver to wait, handed the baby out the window and watched as she was delivered back to her mother, fire brigade-style. I’ll never know if this mother really intended for me to keep her daughter, or if she simply hoped that a few minutes of bonding might result in some other kind of benevolence. Since then, I’ve been wary. Transactions like this fuel rumors of child snatchers and baby sellers that are rampant in Central America.

The infant delivered to my doorstep appears to be sick: weak, febrile, and covered with a flaming rash. I dress quickly and flag down a truck-taxi to take us to the nearest hospital. After a long wait, doctors attend to the baby, though rudely and inefficiently. Their only diagnosis, an infection. I gladly pay for an injection and a prescription, wondering if I might have done as well with my tattered copy of Where There is No Doctor. I try to talk to the mother while we wait, but she offers little. I learn only that the baby was born recently, and her name is Xiomara. Baby X. While I feel as if I’ve averted a crisis, it’s clear that this was not the outcome that the mother of Baby X was hoping for.

A few days later, I walk to Barrio Pomares, the low-lying maze of improvised shacks on the outskirts of town. I’ve brought a small bag each of rice and beans, as well as a pink blanket and a small sum of money for the family. I find mother, baby, and an older woman I assume to be a grandmother in their single room home, its dirt floor turned sticky by the rains. I’m not sure what kind of reception to expect, but I meet with the familiar downcast eyes and uncomfortable silence. I ask after the baby’s well-being and tell them to let me know if they need something more. Cualquier cosa. Anything at all. Baby X sleeps soundly while I’m there. She doesn’t cry. I do.

A few weeks later, Maria Auxiliadora and I are unpacking books that have arrived for the children’s library. A book emerges with a green cover that has a tiny bird sitting atop a dog’s head. I recognize it as the Spanish translation of Are You My Mother?, the popular children’s book by P.D. Eastman. It is the story of a bird who hatches in an unattended nest, and goes in search of its mother, approaching a cat, hen, dog and cow with the question: “Are you my mother?” After a book full of adventures, mother and hatchling are happily united.

I hadn’t yet told Maria Auxiliadora what happened, but when I see the book title, my story spills out: the early morning knock, the hospital, my visit to the baby’s home. Maria Auxiliadora smiles smugly, and nods. “Nando,” she says. She studies my expression, awaiting my reaction and possibly wondering whether I am capable of comprehending the miracle before me. I pause for a moment, my mind swirling like the butterflies we’d encountered on the trail. Of course, Nando. I hadn’t even considered the connection.

Was this really the work of the miracle man of the mountains, or simply a strange synchronicity of events? Had Maria the Helper arranged for Baby X to be delivered to me? If so, why did she choose to give Nando the credit for her generous deed? Until this moment, I felt comfortable with my decision to treat the baby’s illness and to keep mother and child together. It seemed the right thing to do. But in Maria Auxiliadora’s eyes, I saw the same look of deep disappointment that I’d seen at the home of Baby X.

Though we continued to work together, our friendship never flourished, perhaps because in her mind, my choice not to accept the baby was evidence of my disbelief. Disbelief in the Virgin Mary. Disbelief in a crusty old man who spewed profanity, spit in my ears, and prescribed bags of bark. Disbelief in miracles. What then, did I believe in? Perhaps in the healing power of color, movement and light. Perhaps in Blue Morphos, I decided. Though I never went back to Nando’s place, I did return once to look for the butterflies. Sadly, I didn’t find them.

Jane Hall enjoys writing about the moments - sometimes delightful, sometimes difficult - when cultures collide. Recently retired, Jane taught English as a Second Language (ESL) for many years, in the U.S. and abroad. She has a degree in Journalism from University of Wisconsin-Madison and is currently pursuing a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Creative Writing at Hamline University. Her work has appeared in Chicken Soup for the Traveler’s Soul and DRIVE Magazine.