I type my name underneath his, then backspace it all. I stare at the blinking cursor, at the 421-page manuscript, at the decades of memories. Then I close my eyes and let the image of the red and yellow leaves of the Arkansas trees flit across the insides of my lids.

When I first learned about my grandpa’s book, one of his brothers said the manuscript was lost, but years later, someone miraculously recovered it. When I did get it, finally, delivered to me in a USPS box, I sat alone on the floor of my apartment in Fort Worth. I wanted this moment to myself so I could breathe in the pages and feel him with me. I’d been waiting four years.

As an editorial assistant at a book publisher, I work with manuscripts practically every day, but this one was different because it was my grandpa’s novel. He typed this story using WordPerfect on his Leading Edge PC and portable Toshiba and finished it in 1987. He never submitted it for publication again after the Scott Meredith Literary Agency sent him a six-page rejection letter, which I had read before I had even seen the manuscript. So when I opened that box and pulled out those pages, my heart was pounding and my hands were shaking. I carefully smoothed out the pages of my grandpa’s lost book.

The story begins with Jimmie Bailey visiting the Anna B. Wilkins Home for Children, his childhood home in Little Rock, Arkansas, from the years 1935 to 1944. Jimmie’s father, a Communist, left Jimmie and his older brother at the orphanage during the Depression, while Austin Bailey stirred up Communist propaganda in Little Rock. I can picture my grandpa writing these words as he imagined four-year-old Jimmie crying and begging his father not to leave him at the orphanage.

I had only ever cried that hard once in my own life – at my grandpa’s funeral. In fact, my childhood was quite the opposite of Jimmie Bailey’s. My parents were always there for me. My sisters and I are best friends. My only complaint: I only ever had one grandparent. But I had Grandpa Phil, and he filled the void of three other grandparents.

Grandpa Phil lived in Des Arc, Arkansas, where he had a small one-story house. My family stopped visiting his house after we found ourselves sharing the futon with some mice; instead, Grandpa drove to us in Texas. But despite the furry friends, I loved going to Grandpa’s house. He had the biggest sweet tooth and a closet full of cookies. A simple man, my grandpa liked books, movies, boiled eggs, plaid shirts, and gin. When my grandpa visited us on holidays, he always brought a box of Queen Anne’s Chocolate Covered Cherries. Even though I can barely stomach the sickeningly sweet taste of those cherries, I still eat one every year.

I learned a lot from my grandpa, like how to act as awkward as possible in social situations and how to curse – all the important secrets to success in life.

“Goddammit!” He would curse at the TV.

“Dad, the girls!” My mom would shout while pointing at our three innocent heads.

He’d cover his mouth and lean back in the old rocking chair. “Shit, sorry! Oh damn, I mean shit, sorry.” His face would turn as red as those cherries as we girls giggled on the couch.

He had no idea how to talk to us kids, and I was so quiet he could never hear my responses anyway. Usually, we would sit at the kitchen table with him while he read or drank a glass of gin. We would sit in silence until one of my sisters looked at me or vice versa. The eye contact would spark a fit of uncomfortable giggles, and the moment would end with Grandpa asking “What? What happened? Why are you laughing?” Which, of course, would send us in another round of laughing fits. I think making us girls sit at the table with Grandpa was our mom’s way of encouraging us to get to know him – an opportunity I never appreciated.

But despite his social awkwardness and cursing habits, he was my grandpa. Before our Christmas gifts became $20 bills, one year he gave me a giant stuffed teddy bear dressed in a Santa Claus outfit – the last Christmas I so desperately wanted to believe Santa was real. I still have that bear. My grandpa bought me my first set of stationery and always encouraged me to write. Though I had no idea at the time, my aspirations to be a writer were dear to his heart. He drove all the way from Arkansas to attend my fifth grade graduation and hear my speech. My grandpa read every high school newspaper column I wrote and provided me with books and encouragement to become the person I wanted to be and am today. Even though he read so many of my stories, I never read any of his. That is, until I found myself sitting on my bedroom floor, hands trembling as I devoured his manuscript.

As much as I knew about my grandpa, I never really knew anything about his life until after he died. He died suddenly, slipping on the steps of a bus taking senior citizens to Walmart. He hit his head on the cement and never fully recovered. He was 80 years old. My mom and stepdad rushed to Arkansas to be with him in his final hours, leaving eighteen-year-old me at home with my thirteen-year-old sister. When my mom called me that night, I could tell she was trying to sound strong when she said, “Your grandpa passed away today. He wanted us to let him go. Will you tell Lily?”

When she hung up, I think I was in shock. I didn’t cry because it wasn’t quite real to me. Grandpa was supposed to be visiting next month for Thanksgiving. I was going to tell him about the colleges I was applying to.

Lily and I sat at the top of the stairs. “Mom just called,” I began. “Grandpa…” my voice wavered and I quickly took a breath and steadied it. “Grandpa didn’t make it. He passed away.” We sat there hugging, and my younger sister rested her head on my shoulder and bawled in the same way I later imagined little Jimmie crying when his father left him at the orphanage so many years ago.

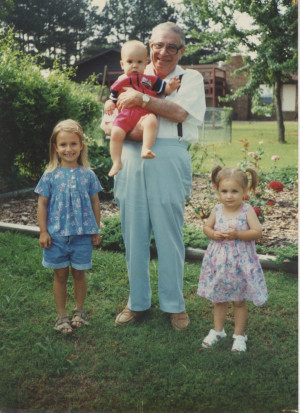

As my sisters and I drove to Arkansas for Grandpa’s funeral, the conversation rode the tidal wave of our emotions. We told stories we recalled from our childhood, reminiscing on Grandpa’s baby blue pants, plaid shirts, and his endless supply of suspenders.

“I’m going to miss his big goofy glasses,” I said.

“And those three hairs that he would comb over his bald head,” Lily added.

“Do you remember that time we ate like three oranges in silence because Mom wanted us to just sit at the table with him?” my older sister asked. “We were all too awkward to make conversation.”

We chuckled while each of us drifted from the conversation to reflect on our separate memories of our grandpa. I leaned my head against the passenger seat window and stared at the beautiful red and orange leaves of the Arkansas trees. I could see him in those trees, an unsuspecting beauty amongst a vast landscape.

I felt a tightening in my throat as I held back the tears I wasn’t quite ready for yet. I wanted to hug that Santa Claus bear and bury my face in its white fur so I wouldn’t have to face the sympathetic stares the next day.

At the funeral, we heard stories about my grandpa lending money and donating his time and assistance to those who needed care. I thought of my car back home, which he had given to me after I totaled mine. He said he didn’t really need to be driving anyway. It hadn’t occurred to me then to think about how giving up his car changed his life, how that meant he’d need to take the bus to get anywhere now. How he would need to get on that bus to Walmart. “You never know a person’s story,” my grandpa would say. “All we can do is help.” All he did was help. I hadn’t even realized I was crying until someone passed me a tissue.

As I read my grandpa’s manuscript, my eyes welled up just as they had then at his funeral. The main character, Jimmie, was alone in the world. Though he was abandoned by his own family, he persevered. He made a new family, a home of out of the orphanage and brothers and sisters out of his fellow orphans.

After hours of absorbing his 421 pages, I sent copies of the manuscript to family members and set about editing it. Not long after, I went to dinner at my mom’s house.

“What did you think of grandpa’s novel?” I asked my mom.

She paused. “I didn’t read it,” she said as she continued preparing our dinner without looking up at me.

“You didn’t read it? Aren’t you curious about your own dad’s book?”

She didn’t respond.

I continued, “Why didn’t you read it? Was it too long?”

“No, I just couldn’t,” she said.

“You haven’t had time?”

“No, Molly.” She stopped ripping the spinach leaves to fragments and finally looked up at me, tossing her brown hair out of her face. “No, I didn’t read it because it’s too hard to read about his childhood. I heard some of the stories growing up. My grandfather was not a nice man. He left your grandpa and his brothers and sister in an orphanage while their mother was dying.” She took a deep breath, trying not to cry. “Your grandpa has been through a lot, but he was a great man despite it all.” She wiped her eyes.

I mulled her words over in my head. “Grandpa is, was, Jimmie Bailey?” I asked quietly.

My mom’s hazel eyes met mine. Holding my gaze this time, she said “Yes, your grandpa was raised in a children’s home during the Depression and the Second World War. You didn’t know his book was a fictionalized account of his life?”

I shook my head and muttered a weak, “No.”

She said, “Sad, isn’t it?”

Guilt had suddenly killed my appetite for both food and talking.

That night I went home, powered up my laptop, and opened up my grandpa’s manuscript, “De Facto Orphan.” I had spent hours objectively reading it, editing it, and rewriting my grandpa’s words to make a “better” story. But that night, I read it all again. I read through new eyes and with a mind that knew the truth behind the fictional words. I read it as my grandpa. I read the part about Jimmie sitting at the window every night waiting for his dad to come back. I read about Jimmie being so distraught that he couldn’t afford to bring cookies to school for a bake sale and thought of my grandpa’s pantry full of cookies. I cried when Jimmie’s aunt brought his older brother home with her but refused to take Jimmie. I couldn’t imagine my sisters abandoning me like that. When Jimmie’s father made the FBI Wanted list for being a Communist, young Jimmie found himself torn between his father and the law. Every time Jimmie cried, I cried, imagining my grandpa as that young, broken, de facto orphan.

But my grandpa wasn’t one to be helpless; he was one who helped. So he turned his story around. He made a family at the orphanage. He went to college, joined the army, and got a law degree. He had a beautiful wife and four children. When his wife got sick, he did everything right, and still the tumors spread and got worse, but just as little Jimmie persevered, my grandpa persevered. And when my grandmother died, my grandpa still had this manuscript in which he had typed his life so that others might feel the strength of young Jimmie Bailey and grow from it.

So after all these years searching for my grandpa’s manuscript, reading his story, and editing the words, I find myself staring at the blinking cursor on the title page, reminding me that this manuscript is not my story. The story of my grandpa – of little Jimmie – is just like the red and yellow leaves of an Arkansas tree: something different, something unique, something beautiful. So after I delete my name, I take a deep breath and type again. Underneath my grandfather’s name, Philip A. Piety, I add

edited

by Molly Spain and somehow that seems right. Like my grandpa said, “You never know a person’s story. All we can do is help.” This is not my story to author – all I can do is help my grandpa’s story live in print.

Molly Spain works as an editorial assistant for TCU Press, a small book publisher in Fort Worth, Texas. She received a BA in Journalism from Texas Christian University and a Certificate of Publishing from the Denver Publishing Institute, and she is currently working towards a Masters of Liberal Arts. Molly enjoys writing, reading, and traveling. “Behind the Fiction” is her first published story.