It’s a random Tuesday, and I’m working swing shift at the county jail. My radio squawks. I tilt my head to my shoulder to hear the traffic from the mic attached to my uniform epaulet. I hear a male voice, breathless and agitated, “Medical emergency in 4 North, I have one hanging!”

I’m approaching a housing module to pick up an inmate and transport her to another part of the jail. I see the module officer through the window and signal that I’ll be back later by holding my finger in the air. As a response escort officer, it’s my job to respond to emergencies. Suicide calls are the worst.

“CCR to staff, we need a response to 4 North, medical emergency, one hanging,” central control repeats. Three women sitting in a dark control room in the bowels of the jail, surrounded by closed circuit camera monitors and computer screens, set the emergency tones and begin pushing buttons that open doors for responding staff. The tones begin. “Beep…beep.” All emergencies are a little scary, whether it’s hauling inmates to the hole after a fight breaks out, or getting a combative inmate into his cell, but hangings are a special kind of frightening.

The jail is two jails, an old one and a new one, connected by a skybridge the length of several grocery store aisles. The stainless steel elevator doors open, and I push the button for the D floor, where the skybridge is located. The inmate I was about to pick up is in the new jail, the emergency in the old. A lot of ground to cover.

When the doors slide open again, I take off running. A nurse gets off another elevator and runs to the medical clinic to get the crash cart.

Hanging…that’s a call you hate to hear. Just like “I’ve got a jumper.” Another bad one. Sometimes they’ve already jumped and they’re lying in a broken bloody pile when you arrive. Often though, hangings are caught so quickly that the person barely has time to lose consciousness. I’ve rushed to hangings before—totally expecting the worst—but found the inmate had been cut down by the module officer and first responder and was alert and breathing by the time I arrived. Since they walk the tiers every thirty minutes to do welfare checks in 4 North, I’m hoping that’s the case this time. My adrenaline doesn’t start pumping yet, but my heart rate is up from the exercise.

I’m sucking wind by the time I turn the corner at the end of the skybridge and proceed to the door that leads to the old building’s elevator bank. While I’m waiting for CCR to open the door, I hear rapid footfalls coming down the hall behind me. Once the door opens, I hold it for a parade of responding officers, followed by two nurses pushing the crash cart—a typical scene for an emergency.

We’re crammed shoulder to shoulder, chests heaving—trying to control our breathing so nobody knows what bad shape we’re in.

“Sounds like some of us need to hit the gym,” someone says.

“There are obviously no minimum standards for physical fitness here,” someone else chimes in.

“I ain’t givin’ any of you jokers mouth to mouth when you fall out,” a third guy says.

We chuckle. In tense situations, it helps to remain light-hearted.

We all file through three more doors and finally into the unit. “Get the defibrillator!” someone yells from the upper tier. The nurses grab it off the crash cart and run up the stairs leaving the cart behind.

Most of the officers are just standing, assessing the scene. Since it’s a maximum security unit, the inmates are already locked down. Our job is to make sure they aren’t gawking out their cell door windows.

“I need a mask!” a nurse yells. I open the cabinets in the crash cart, which has shelves and drawers filled will forceps, syringes, gauzes, EpiPens, glucose tubes, and many things I can’t identify—none of which apply to this situation—until I find a drawer that I recognize as CPR stuff. I grab the bulb-thing that you use for respirations, a couple of different types of masks and oxygen hoses, wrapped in plastic, and then unhook the oxygen tank from the outside of the cart.

I’m trained in CPR, First Aid, and Automated External Defibrillator, but I’m not trained on administering oxygen or how the crash cart is set up. I adjust my load, careful not to drop the oxygen. I race up the steps, my heart pounding.

I enter the cell, set down the tank, and hand the bags of equipment to a nurse. She begins hooking up the oxygen while the other is securing the AED pads to the inmate’s chest.

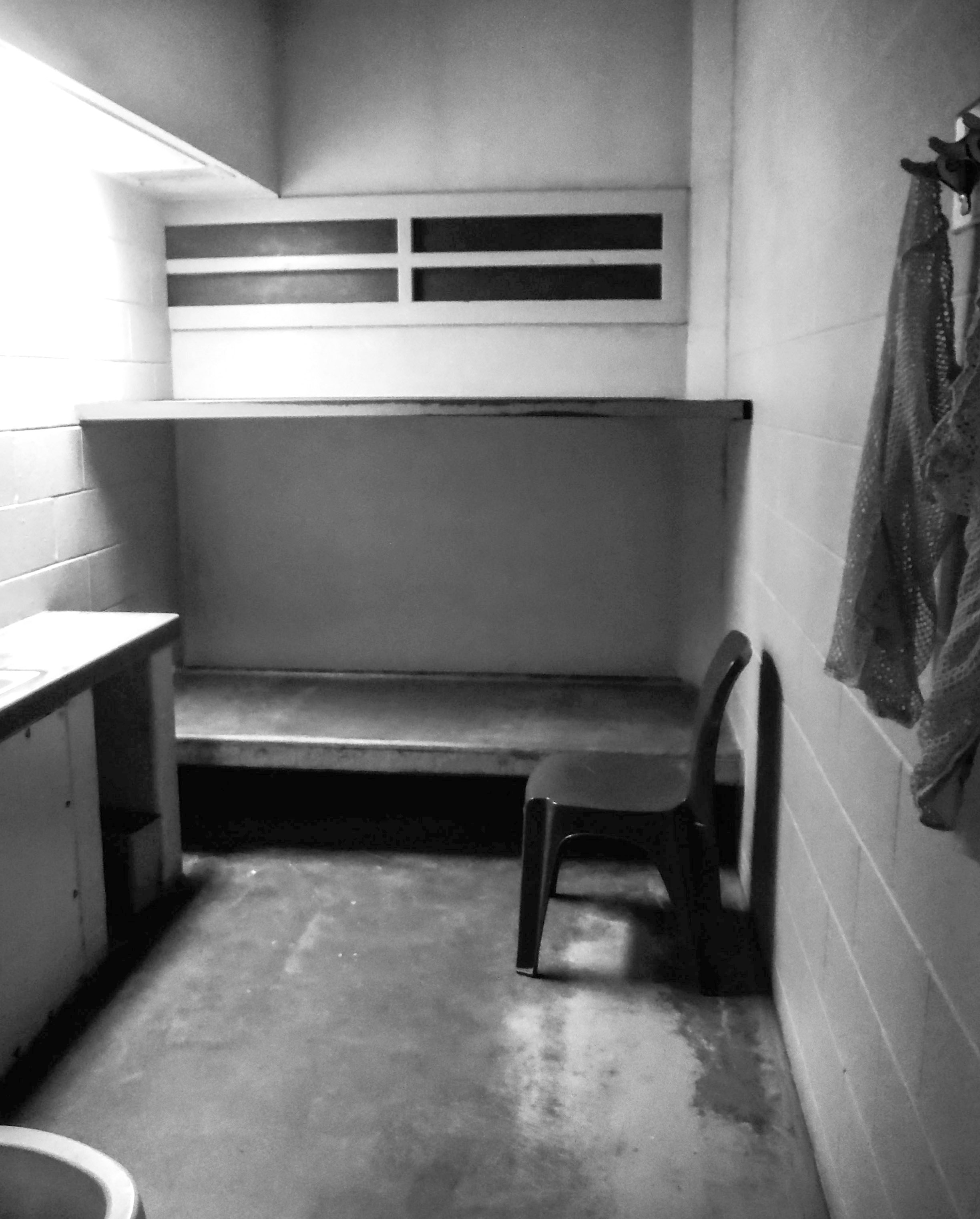

In this dreary, stark concrete cell, there are two bunks attached to the far wall with the paint worn away in places. Graffiti is etched into the thick metal surrounding the narrow windows above the upper bunk, backed by blackness at this hour.

A sheet dangles from the upper bunk, knotted. Woolen blankets are piled on the thin plastic mattress of the lower. An empty bin box sits under the bunk. There would be a few jail-issued hygiene items lying on the counter next to the sink. A mini deodorant. A shampoo bottle. A bar of soap. But I notice none of this, because all I see is the young man who has been taken down from the sheet in which he was entangled and has been placed on his back on the floor. He’s not wearing a shirt. The waistband of his underwear is showing above that of his green uniform pants. His feet are bare.

He’s just a kid, young, and narrow about the waist. His skin is pure—unblemished by time or age. The hair on his face and torso is sparse. An adolescent.

His color is good, but he’s unresponsive. I know he must be lacking in pulse and respiration since the nurses are starting CPR.

Once the sticky pads are affixed to his chest, the nurse pushes the button on the bright green plastic AED unit to activate it. A robotic female voice says to commence CPR. One nurse holds the mask to his face, runs the AED, and calls the numbers for breaths and compressions. The other nurse squeezes the plastic bulb respirator, and an officer, an athletic young war veteran—one of the two working in the unit who had helped bring him down—interlaces his fingers, one hand on top of the other. He places his hands on the sternum of the young man and begins rhythmically compressing the inmate’s chest, elbows straight, his entire upper body rocking into the movement.

This team is working like they’ve done this a thousand times. Even though we’re all crammed into the small space, I stand behind the other officer, ready to jump in on compressions if he becomes fatigued, but his adrenaline is coursing through his veins and he performs like a rock star.

A sergeant called 911 when we arrived on the unit and the paramedics will be here soon to take over, but it feels like we’re on our own for eternity. Occasionally the AED instructs them to stop CPR, to check the patient, to administer a shock. Three times this happens, and each time the shock is administered, the body jumps, and we wait for a pulse to be detected. Each time: nothing. “Continue CPR,” the automated monotone voice instructs.

I wait for the other officer to get tired. I’m ready to step in. “Your doing great,” I say, my own back getting tired from the angle at which I’m forced to stand wedged into the corner of the cell. “You’re almost there. Aid’s on the way. I’m here when you need a break.” But he keeps going, giving compressions like he was born to do it.

They’re keeping his lungs filled with air. They’re bringing oxygen to his brain. There is hope that he will live, but his eyes say something different. They’re half open and they sparkle. It’s as if they’re made of crystal. They don’t look real. They look lifeless.

The fire department arrives and takes over the operation. Five muscular men in pressed black slacks and tight navy t-shirts emblazoned with red fire department logos storm up the stairs carrying their emergency kits that resemble giant tool boxes. They pull him out of the cell so that he’s lying on the walkway of the upper tier where there is slightly more space. They gather around and start hooking things to him. The rest of us, now empty-handed, relieved of responsibility, step back and let them work. They shoot him full of medicine to start his heart. They start an IV. They continue CPR. They monitor, and they do everything they can. And they keep doing it. Until they finally determine, nearly an hour after the initial emergency call, that he cannot be revived.

From downstairs where I’m now standing with others, quietly talking and hoping, I hear, among other voices and commotion, “Time of death...”

The optimism pours out of me, leaving me deflated as my relief taps me on the shoulder. It’s after midnight, and I’m handing over my keys and radio and giving him the disturbing turnover.

My shift is over.. While it doesn’t seem right to leave before they take him away, I can’t stay. I need to go find a computer and write up a report before I go home.

As I get off the elevator and start the long walk across the skybridge, I see the guy who’d been giving CPR walking ahead of me at the other end. A graveyard officer is coming the other way and asks him how his shift was. He replies, “I need a drink.”

When I get home, I’ll be having a drink or two as well. A night like this, there’s no sleeping. All that adrenaline is still working its way out of your system, and you lie in bed replaying the events of the night—the things that are done and said. You try to determine if there was anything you could have done differently, and finally you come to the unanswerable question…why had it happened? Why?

I sit down at a computer and open the young man’s file. I need to get his inmate number for the report. But I look through his record for answers. He was a first-timer, just there on a petty misdemeanor offense. He would have gone to court, and he would have done probation or paid a fine and gotten on with his life. Then I see his birthdate. He was only nineteen years old. Nineteen. I’m the mother of a nineteen-year-old, and I know she struggles. It’s hard to be nineteen. I was nineteen once, and I was suicidal. “Nineteen...” I whisper under my breath and curse.

It’s well after 1:30 a.m. when I get home, pour myself a Black Russian, and go out to the porch to let the late summer chill cool the heat of the blood rushing through my arteries. I sit and look at the stars and replay the events of the night in my head. Seeing that kid’s eyes devoid of life—devoid of hope—I remember how I felt when I was his age. I’d struggled with depression for a few years. I had low self-esteem, few friends, no ambition, and no interest in the things I once enjoyed.

It was like living in total darkness with no hope of seeing the sun again, fumbling my way through life without being able to see any of the beautiful things that make life meaningful. I felt no hope for the future. I couldn’t see a point to any of it. I wanted to end it. When two childhood friends committed suicide in fairly short succession, I envied them.

I think about those boys all the time—even now, especially today—almost thirty years later. I cry for them and the lives they never got to live. I wonder what they would be doing now. I think about the lovers who were never given the opportunity to love them, the children who didn’t get to have them as fathers, the things they might have accomplished, and the lives they would have touched. I think of the marks they would have made on the world. They could have achieved greatness and lived long and happy lives.

Not once have I ever pictured them as fat or lonely or unhappy, or as underachievers or loners or paupers or alcoholics, or working in jobs that they hated or spending time with people they didn’t much care for. Never did I picture them struggling to get by or showing up at dead-end jobs so they could pay the bills.

I shiver and pull my jacket tight around me. I couldn’t save Paul or Tom, and I couldn’t save the kid in the jail, but I wonder if I can save myself. I want to honor them by being the person I hoped they would have been.

As terrible as suicide is, as tragic and devastating as it is to those who are left behind, as unfortunate as it is that the dead will never get to make their mark or do what they were born to accomplish, the real calamity is sticking around year after year and not really living.

They left with all of the potential, and I stayed and squandered it. I look down at my uniform, the one I have been wearing five days a week for eight miserable years in that jail. What would they think of me, if they could see me now? I’m not even crying for Tom and Paul or that boy anymore. I’m crying for myself.

I wipe the tears spilling from my eyes with the back of my hand, and I pour a second drink. I no longer notice the chill in the air. The ice in my glass clinks as I take a long pull. My mind and body begin to relax. It finally occurs to me why I am so sad thinking about those boys. It isn’t just because of all the things they never got to do, or because I’m jealous that they had the balls to do it, and I didn’t. It’s because I stayed and didn’t live my best life.

Mary Senter received her MA in strategic communication a year after this story was written. She left corrections and now works in communications and design for local government. She holds certificates in literary fiction writing from the University of Washington and writes literary and historical fiction. She’s also a fan of the personal essay. Her work can be found in FewerThan500, WORK, Red Fez, Stratus: Journal of Arts and Writing, and Heater. She is working on an historical novel set in the 1890’s. She writes in a cabin in the woods on the shores of Puget Sound. Visit her at: www.marysenter.com