It is a pretty summer night. My six-year-old son Christian and I are on our way home from his swimming lesson, and the sun is setting to our left in hues of pink and purple. We are content until we come upon a cluster of mallard ducks trying to cross the two-lane road. Drivers in both directions slow and carefully veer onto the left and right shoulders to avoid them, while the ducks turn their heads in all directions, looking for a way out of their predicament.

People are patient, admiring them from their windows, until the driver of a clunker speeds around from behind us, stomps on the gas and hits them, his intent obvious. His car spews loose asphalt as it plows through the ducks, forcing some to loft into the air and scatter, while leveling one, a male, who now sits damaged before our front wheel.

I curse the offender under my breath while he races away, his tires screeching. I can see him and his teenage passengers through his back window, throwing their heads around and laughing, proud of this act of defiance.

Christian stays silent, his eyes monopolizing his face as he watches me stop the truck and get out. We are conscious of the cars backed up behind us, and of the stream of gawkers now passing in the oncoming lane. They slow, but no one stops to help; some of them drive off the road to the far side to provide me space.

The injured duck sits dazed on the pavement surrounded by tufts of his own feathers, surprised at his sudden circumstance. A wound bigger than an egg oozes a pinkish-red on his side, and one orange leg with its webbed foot juts out from his body like a broken mailbox flag. I lean over him, heartsick and angry, trying to figure how I can scoop him up without causing further injury. I reach for the duck slowly, so as to not frighten him. He makes no effort to evade my hands. I expect a certain heft when I lift him, but he comes into my arms weightless as a sponge. Without protest, he allows me to carry him to the truck.

“Hand me your towel,” I say to Christian as I open my door, and he complies. It is still damp with pool water. I spread it on the seat between him and me and set the duck there. My son looks at me earnestly and says, “I have always wanted a duck,” as if I have at last read his thoughts, seized an opportunity, and accommodated his wishes, like when I purchased his first pair of figure skates.

His comment catches me off-guard. I pause for a moment, look him in the eyes, say: “I’m taking this duck to the clinic.” If Christian is disappointed, he doesn’t let on.

It’s all I know to do. It’s a Friday, and I’m sure Dr. O’Neill will be at his after-hours clinic, just a few miles away. He’s a generous and clever physician, and I believe he’ll treat the duck with the same care he uses to treat the cows and dogs on his farm. He told me once when I was a reporter, interviewing him for a newspaper article, that he oftentimes takes animals into his basement, bandages them, and gives intravenous medication when necessary. I think he can bind the broken leg and bandage the duck’s wound.

I turn the truck’s ignition back on, engage first gear and pull into traffic, and the duck accepts this without stirring. He aims his yellow bill toward the dashboard; his eyes are two glistening ebony beads. Sometimes he turns his head to the left or right, as if scanning the dials for information. I imagine he’s wondering about his destination or about the fate of the other ducks.

Christian sits in the passenger seat with his hands in his lap, but I can’t resist the urge to pet the emerald head. I stroke my right index finger across the silk slope of it, fantasize that my touch comforts the duck, like it does Christian when he’s fallen and skinned a knee.

As I drive, I’m careful to balance a safe speed with my urgency. I have no sense of the duck’s internal injuries, and am sure he must be in shock. I hurry as fast as I dare, shifting my glance from the road to the duck to my son and back again. It feels like forever when we are forced to become part of a line of cars poking along, single file, toward a red light. This one long road and two right turns are all that lie between Dr. O’Neill and the duck’s salvation.

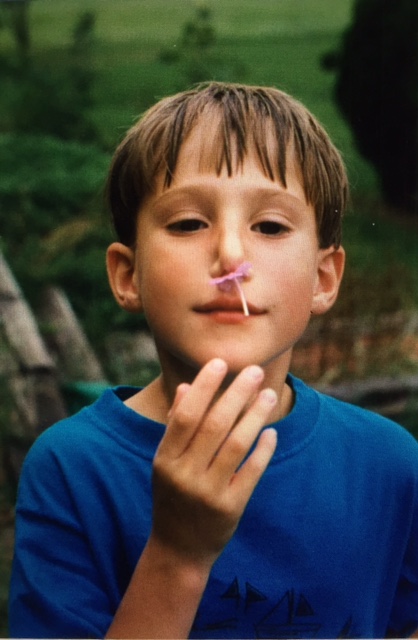

Sincere and sensitive, Christian rides with his head poised atop his slim, erect neck, his fingers extended atop his thighs, his limbs long and slender.

We travel maybe ten minutes like this, to just short of the clinic, when the duck starts. He elongates his neck and thrusts his head forward, as if preparing to launch. He lifts one lovely wing and fans it open, its brown and white feathers spread wide; the tip brushes the steering wheel. He flaps the wing so that it is heartbreaking, and then he lays it beside him, still open. Each feather is perfectly formed and aligned. He rests his head, folding it gently down onto the arc of the wing, his bill and one eye facing the sky that shows through the window.

Without having issued a sound, the duck goes still. Christian and I watch while death comes into our truck and assumes the duck’s form. It lies between us, tangible and oddly beautiful, as I turn the truck toward home. Christian breaks the silence when he asks, “Why hasn’t the duck gone to heaven?” I turn to see his eyes imploring me. He looks sad and confused, and I feel at a loss for what to say. And so I say nothing.

I wonder if dismay registers on my face as horror. I have always explained heaven to him as a place where beings join God when they die. My explanation, I have always hoped, served to offer comfort while deflecting death’s ugliness. Having never seen death until this moment, though, Christian has clearly understood me to say that heaven has a tangible, physical presence, and that the body’s ascension is instantaneous.

I bounce the car up the driveway’s small incline, the headlights playing off the tools in our garage. By now, the sun has given its benediction and nightfall is near. I spot my husband, Don, off to the side of the house, putzing around atop the three-layered terrace we constructed from railroad ties one spring. He is clothed in the uniform he wears to his electrician job: a white undershirt, and brown work pants that cover the tops of his Brogans. He looks a bit like a caricature, the boots weighing down his body, so slim it seems it could be tossed by the wind at any moment. He presses the branches of a tomato plant to one side to look for its fruit, pulls the occasional weed from the rock-pocked earth packed around the roots.

I exit the car and step over to tell him what’s happened. Christian makes his way out of the truck to where I stand with his father. The two of them listen as I say, “A car deliberately struck a duck up on Sashabaw Road. I’m so disgusted that anyone could be so cruel.”

Don, an animal lover, shakes his head in disbelief. “Sons-a-bitches,” he says.

I explain how we headed for the clinic but didn’t get there in time, how the duck now lies dead in our truck. Don is an unassuming man, a stoic, the type who accepts what comes without complaint, making few demands, offering few comments or opinions. It doesn’t surprise him that I have brought home a dead duck, nor does it surprise him that the burial task will be his. The burying of pets has always fallen to him. He nods his willingness and goes to fetch a shovel.

It never occurred to me that Christian believes bodies go immediately to heaven. My daughters never responded this way. Filled with their little girl sadness, they cried when their cats died, but went on about their business when their father carried the animals to our yard and commenced digging. That is all the experience I have to go on.

I worry that Christian thinks of me as a liar as I venture into the house and rummage for a box that will make a suitable coffin. Rather than save a discussion about death for a time when he and I will be more prepared to deal with the topic, I know I’ll now have to stand in our garden and explain its intricacies. I find a Birkenstock box in the girls’ bedroom closet. It’s sturdy and the perfect size. Taking it out to the truck, I fold the duck inside it, pressing his feet onto the floor of the box and his wings alongside his body, curving his neck and head down onto the pillow of his feathers.

Christian and Don watch as tears drip from my face to seek comfort in the feathers too.

After I have closed the lid, I place the box near Don’s feet, then move next to our son. Christian is motionless and forlorn as a scarecrow on a windless day, still in his swimsuit, arms clamped at his sides, the retreating sun making washboard shadows of his ribcage.

We watch Don survey the terrace for an appropriate spot on the middle tier, beneath the radishes and what was once a row of carrots, stymied in their growth weeks ago when their green tops were sheared by a rabbit who ambled through. Don kicks one boot against the ground to test how well it will give. Then, his chin curls to his chest, his shoulders move forward, and his strong arms force the shovel blade into the dirt again and again, each lift bringing stone-clogged sand up and out until the hole is three or so feet deep.

I bend down to Christian, his form a miniature of Don’s. He is studying the situation, considering every sight, sound and gesture that accompanies this moment.

Christian fascinates me. His ears take in the slightest of sounds, his nose the scantest of scents. He has an eye for color and detail, a mind that is curious about everything from whistling whales to the need for earwax. Already, he has asked me an untold number of questions, and absorbed my answers, always, with absolute seriousness.

Fancying Christian some kind of prodigy, I do not yet know that a touch of autism informs his experience of life, that this is why his senses are on high alert, why he takes things literally.

“Our bodies have souls,” I begin. “Invisible parts we cannot see.” His gaze fixes on my face as I try to summon words to explain this abstraction. I hold a blue and white picture in my mind of what heaven looks like, the same picture I have carried since my own childhood. “Heaven is a beautiful place where we will see our loved ones again.” I hear my words float into the air, wonder if they evoke a pretty scene for Christian as he listens. He doesn’t share what he’s thinking, and I don’t ask.

When Don is finished, he lowers the duck into his resting place, scrapes dirt back into the hole and tamps it down. I coax our son toward the house while he puts the shovel away. Touching Christian’s cool, moist shoulder, I escort him through the garage to the kitchen door. He moves at my pace, obedient.

“It’s okay,” I say, as much to reassure myself as to reassure Christian. We step over the threshold, and he tells me he’s hungry. I go about searching the cupboards for something to eat, while he wanders off to change into his pajamas. I watch the back of him walk away from me. In the absence of conversation, I imagine I hear acceptance in his footfalls as they softly tap the carpeting en route to his bedroom. Behind us, the stars have begun to show themselves, one by one.

Carolyn Walker is a memoirist, essayist, poet, and creative writing instructor. After working twenty-five years as a journalist, she returned to graduate school and earned her MFA in Writing degree from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2004. Her work has appeared in The Southern Review, Crazyhorse, Hunger Mountain, The Writer’s Chronicle, Gravity Pulls You In: Parenting Children on the Autism Spectrum, and many other publications. Her essay “Christian Become a Blur” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and reprinted in the 50th anniversary edition of Crazyhorse. In 2013, she was made a Kresge Fellow in the Literary Arts by the Kresge Foundation. She is a lifelong Michigan resident and the married mother of three grown children.