Sam brought home the cherry red Yamaha one Friday night, the summer everyone was dying. He was straddling the motorcycle and revving the engine in the garage when I came through the kitchen door. He looked at me sheepishly, as though he thought I might say something about the expense, but I didn’t. I put down the dishtowel I was holding and said, “Take me for a ride.”

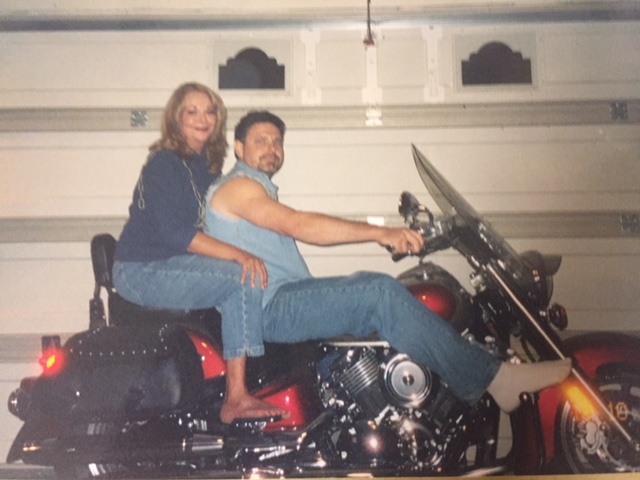

Sam showed me where to put my right foot and I swung my left leg over the body of the bike and settled into the seat behind him. I put my arms around his waist and we glided out of the garage, out of the neighborhood, and onto a soft blacktop road that would take us into the country. The day had been hot and humid and the air was still warm and moist at the tops of the hills, but the valleys were as cool and dry as the inside of our Frigidaire. I could feel the wind, lifting my hair, drying the sweat at the nape of my neck. We went on that way that first night, climbing hills, descending into valleys—warm, cool, warm, cool, warm, cool—for a couple of hours. Just him and me, under a moonless sky strewn with stars.

We’d tried other ways to get away from it all, like taking the boat down the Verdigris River, but Sam’s out-of-state brothers and sisters would call his cell, one by one, for an update on his dad’s, his mom’s, or his sister’s condition. Could they send us some money for a part-time nurse? they asked. Or a housekeeper? Sam would cut the boat’s engine to hear them better and we’d idle there, in the middle of the river, under the hot sun.

“We could use another set of hands,” Sam would begin. I’d settle back against my seat, pull the brim of my straw hat further down my sweaty brow, and listen, while the boat made lazy circles in the water.

What Sam’s brothers and sisters really wanted was reassurance they weren’t bad people for not being here. Sam’s dad, at 88, was failing, his mother, 81, was dying of ovarian cancer, and his youngest sister, not yet 45, had terminal lung cancer. Sam had one other sister in town. She and I had both taken leaves of absence from our jobs to deliver meals, manage medications, and shuttle my mother-in-law and sister-in-law back and forth to chemo. (When I fell in love with Sam, I’d also fallen in love with his big Catholic family.) Sam, who was still working, had been given power of attorney over everyone’s affairs. He was managing the money, coordinating care, and keeping his out-of-state brothers and sisters updated.

We’d only had the motorcycle five months when Sam’s dad passed away. Sam’s mom stood at the front of the church, wearing a black dress and a black turban to hide her hair loss, and gave his eulogy. “Art was a meteorologist with the National Weather Bureau,” she began. “His was the voice you heard, interrupting your favorite TV program, whenever there was a storm warning.” Her smile wobbled. The hands that held her notes shook from chemo. She swayed slightly on her feet. I don’t know how she found the strength.

That was the week before Thanksgiving. Sam’s family always gathered at our house for the holiday dinner, and this year was no exception. But this year, I bought the roast turkey, the mashed potatoes and gravy, and the sweet potato dish from our grocery store’s deli. Then I transferred the meal from its aluminum foil pans into my good dishes. It wasn’t my best dinner, but Sam’s brothers and sisters, who had stayed over, agreed with me that what was important was we had spent the holiday together as a family.

After that, Sam and I began getting up at dawn on Saturdays and Sundays, so we could spend the mornings on the motorcycle. The bike’s vibration soothed us. Speeding down the back roads, the wind and the sun smoothing our faces, we felt like we belonged to the earth and the wind, the sun and the sky. We were part of nature. When we remembered to eat, we’d stop at some biscuits-and-gravy café with checkered curtains over the windows and have breakfast. I walked bow-legged for the first few steps after I got off the bike, and I could still feel my body thrumming when I sat down in the cafe. We ate so much, you would have thought we had walked there, instead of ridden. It was the fresh air and the forgetting.

Six weeks after Sam’s dad passed away, his mom died. His sister pulled her oxygen cart to the altar at the front of the church to give her mother’s eulogy. “My mother raised seven children and still found time to volunteer at Catholic Charities,” she began. Her voice was thin and raspy. You could hear the effort it took to inflate each word with air.

“That poor family,” I heard someone whisper from the pew behind me.

The trees were bare of leaves now and the temperature was dropping. Sam and I bought leather jackets, chaps, and ski masks and kept riding. We rode down one two-lane highway after another, through one small, dusty Oklahoma town after another. I saw places I wanted to stop and investigate as we roared down the highways—signs pointing to a crafts fair, the entrance to a State Park, the Locust Grove Fried Pie Festival—and I’d lean forward and tug at Sam’s sleeve.

“Let’s stop,” I’d yell into the wind coming over his shoulder. I’d point at the signs.

Sam’s thigh muscles would tighten. He’d shake his head “no” as he speeded past.

Every year, Sam and I had a New Year’s Eve party for family and friends, but I wasn’t in the mood for a party this year. It seemed disrespectful, having a party so soon after my father- and mother-in-law’s passing. Sam and I had admired their marriage so much, we’d gotten married the same month and day that they had. We’d celebrated every anniversary with them. How would we find our way, now that they were gone?

“If we have to have a party, let’s make it family only this year,” I said. “A quiet get-together with family would be spiritually healing for all of us.”

“Spiritually healing?” Sam said derisively. “That sounds like fun.” He’d been staying out late, drinking with friends, since his parents passed. I hadn’t said anything about it. It didn’t seem right, nagging him, when he’d just lost his parents. I didn’t say anything now for the same reason.

“We’re having a party, the same party we always have,” he said.

Sam’s sister died in the spring, just when the first yellow daffodils I’d helped her plant were coming up. Sam wore sunglasses to the service to hide his eyes, dilated from Xanax, and kept them on while his two nephews sang “Amazing Grace.” He fiddled with his key ring as the priest spoke of mansions with many rooms. Family and friends were gathering at his other sister’s house for cake and coffee after the service. I wanted to go, but Sam didn’t. He wanted me to ride with him.

At home, in the garage, Sam tossed his helmet into a corner. He didn’t believe in safety anymore—nothing could protect you from death, he said—and he wasn’t interested in riding through the countryside or exploring small towns. Now he wanted to be on the interstate, leaning into its wide curves, driving as fast as he possibly could. With the hard gray concrete rolling under my feet, I didn’t feel like I was part of nature anymore. I was frightened by the speed.

“Stop holding on to me so tight!” Sam yelled over his shoulder.

The last time I rode on the cherry red motorcycle with Sam, the ride began pleasantly enough. We were putting down a gravel road in the country, parallel to some railroad tracks, on a sunny summer day. Then we heard a train rumbling down the tracks and Sam revved the motorcycle.

“What are you doing?” I shouted over his shoulder.

“Racing that train to the crossing,” Sam said.

“No, Sam. Are you crazy?”

In a burst of speed that almost bucked me off the back of the motorcycle, Sam surged ahead and made a sharp right. We bounced over the crossing just seconds before the train roared past and skidded to a stop in a spray of gravel. Sam laughed out loud, exhilarated by the near miss. Something similar had happened the first year we were married. With Sam at the wheel of our car, we’d slid through an icy intersection, flown over a ditch, and crashed through a barbed wire fence before coming to a sudden stop. For a split second, we just sat there. Then Sam looked at me, I looked at him, and we both burst out laughing.

But I wasn’t laughing now. Sliding through the icy intersection had been an accident. Sam had raced the train on purpose.

I got off the bike, walked on wobbly legs to the shade of a tree, and sat down. “What’s wrong with you?” Sam asked.

“What’s wrong with you?” I replied. “You could have gotten both of us killed back there.”

“I was just having fun. C’mon,” he said, extending a hand to pull me up. “Let’s go.”

“No, Sam. I’m not riding back with you.”

“Suit yourself,” he said, shrugging. I sat, my back against the rough bark of the tree, and watched him ride away.

I’d held on as long and as tightly as I could. We’d had the kind of year that brought a couple closer together or—if the fabric of their marriage was already frayed—would tear them apart. It had torn us apart. It was more than just the difference in our grieving styles. Sam had been a family man, but now he didn’t want to be “tied down.” He wanted to “live like every day was his last.” I wanted to live the same way we’d lived before: hanging out with his family, camping with his family, traveling with his family.

But Sam had lost his family, and somewhere along the way, I had lost Sam. “I’ve changed,” Sam told me a few weeks later as we stood in the garage of our home. He’d gathered most of his clothes and was stuffing them in the saddlebags of the motorcycle. “Losing my family has changed me.”

“You haven’t lost all your family, Sam. There’s still you and me. There’s still your brothers and your oldest sister,” I said. “We can get through this together.”

Sam only shook his head. He raised the garage door and looked longingly down the road.

“I just want to be alone,” he said, throwing one leg over the cherry red motorcycle. “I’m sorry.”

I stood on the sidewalk in front of our house and watched him ride away—again—blinking back tears until the motorcycle’s single red tail light was out of sight. A year later, we divorced.

It’s been several years, now, since I’ve ridden a motorcycle, but I still remember those first rides on the cherry red Yamaha and how they felt. I remember cresting hills at such crazy speeds, it felt like Sam and I and the motorcycle might just take flight. We might fly off into the pink-gold sunset beyond the hill. We might fly straight to heaven, where everyone would be waiting for us. We might all be a family again.

Sandy Kline is a lab coordinator and adjunct instructor at Tulsa Community College in Tulsa, OK. She is pursuing a Masters in Fine Arts in Creative Nonfiction at Bay Path University. She was a columnist/ contributing writer for Art Gallery International, U.S. Art, Midwest Art, and Southwest Art in the 90s, and won a grant from the Tulsa Arts & Humanities Council in 1995. This is her first published creative nonfiction essay. Sandy has two children and three grandchildren, and you will not find her driving or as a passenger of any vehicle with fewer than four wheels.