I flew at night. It was storming. Blustery winds tipped the plane's wings up and down as the pilot asked us to tighten our belts and prepare for a rough landing. When the plane came to a stop, the man in a brown business suit seated next to me looked me straight in the eye and said, "Worst landing I've ever experienced, and I've flown a lot." To me, the turbulence was fitting. The jolts of the plane’s path, and the flames that escaped the engines, drew a map of the lives in my family; a disjointed trajectory, one I imagined littered with all of our bones.

I was dressed as though going on holiday. I wore a crisp white button-down shirt that had collar points of black and white plaid, exactly matching the belted full skirt that cinched my newly slimmed figure. I wore a black hat with a wide brim and carried one bag.

This was not a vacation, though. I was going to Texas to see my daughter; I was going to prevent the rebirth of a legacy I thought I had ended, the one that included stories of mothers abusing daughters, hating daughters and neglecting daughters.

Family lore says my grandmother was a merciless taskmaster, and that my mother regularly took beatings from my grandma “for all the kids.” The next generation of girls – in which I was the oldest of four in my extended family – had all been molested by men who were a steady parade for my mom and my Aunt Ella.*

Long before that, though, I had grown up under the cloud of my mother’s hate, her anger and frustration often finding me. She called me a “little whore” before I even understood what it meant. Sometimes her words were a hurtful barrage of name calling and cursing. The worst times were when I was little and would go to her for comfort, reaching to touch her, cautious of her snake-like ability to strike. Extending my hand, she’d snarl, “Don’t touch me, get your hands off me, you little bitch.” The echos of her words diminished me my entire life.

She landed her last blow when I was fifteen and seven months pregnant. Wrestling away from her, hysterical and broken, I wailed. “I will come back and kill you if you’ve hurt my baby.” I ran out that door, caught a bus to Southern California and within weeks was taken in by my Aunt Mae and Uncle Ronnie. Aunt Mae had somehow survived the brutality of my grandmother and invented a life where her husband and two sons would find happiness in agreeing with their father’s political opinions over meatloaf. The mundane became the marvelous. Her influence, her example, and my own self-determination set me on a path to be a good mother, too. At 15 and without a clue about how to parent, I made a promise to myself: I would be the mother I never had.

As a young mother, I had made one life-changing mistake: the decision to give my two-year-old daughter to my ex-husband during our separation. That young woman who had relinquished her baby girl to her ex-husband was incomprehensible to the mother I was now.

I remember that fateful day, when he and I met at his ramshackle country house, outside in the dry heat of summer. He looked into my eyes and held my hand, his sadness creating furrows and lines in his young face and said, “You know, I’m very lonely. Would you give me one of the kids?” His grieving blue eyes met mine in a plea for relief from the loneliness that was strangling his spirit.

I was struggling to survive on welfare, while going to school and parenting our son and daughter. Our daughter was the youngest but also his biological child, so she would have to be the one. It was too big a risk to let our son go with him; I wasn’t sure my ex-husband’s family would embrace our son as their own. My decision wasn’t swift, and I couldn’t comprehend the weight of the decision I was making. Nor could I have imagined that my ex would ever leave our community and move out of state. But he moved to Texas, taking her with him when she was six years old.

Every year she flew to California to spend June birthdays, Father’s Day and the 4th of July with us. We didn’t do big things. We picked berries and made pies, went swimming at the lake, shopped for school clothes and learned to love each other in a limited amount of time. During those summers, she slowly grew up. She developed crushes on musicians like Adam Ant and let go of dolls and frilly bedrooms. Her arrivals were a celebration; her departures were heart wrenching.

Although I never beat my daughter, once in a fit of anger, I yelled, "I'm going to break your arm!” They were my mother's words, breathing their fire through me all those years later. It was a testimony to a past buried deep within me, a verbal relic of what I had survived.

During a summer stay after the end of 8th grade, I found a letter in her room to a girlfriend in Texas. “...have you ever ridden a guy before?” it asked. I wasn’t sure it confirmed anything, but I knew it was a red flag. Was this the same girl who weeks before had celebrated her 15th birthday with a pie fight in the driveway and a sleepover party?

A few months later, I got the call from her brother, Steven. He was five years older, and she had asked him to call because she was too afraid to tell me.

“Mom, this is Steven. I have something to tell you.”

“Are you OK?” I asked, my heartbeat gaining speed.

“Mom, this isn’t going to be easy.” And then, time hanging, he summoned the courage to deliver a kind of news that no mother wants to hear. “Lisa is pregnant.”

That campaign of syllables, collected into sentences landed squarely in my gut.

“Can I call her, will she talk with me?” I chirped.

Her tearful confession escaped her lips in fragmented sentences and raced over wires from Texas to California: “Eight weeks, positive test, dad wants me to get an abortion.”

Her dad's wife had declared that she would not have another baby in her house. Her youngest child was a teen and she had no intentions of raising another baby. She and I had never had an alliance. And she stonewalled any discussion about the pregnancy or any options.

Someone, a boy, was the father. He was young and sounded like a kid on the streets running wild. No one but Lisa really knew anything about him. He was erased from the scene and never attempted to make an appearance.

Listening to her panic, her sorrow, I was steeped in an inexplicable calm. “Everything is going to be all right. I’m going to help you,” I said.

Now 36, and filled with confidence that had been built on years of putting one foot steadily in front of the other, I now knew how to be a mother, how it felt to be a mother, and what a mother was suppose to do. I knew that I would go to Texas when she had the baby. I knew that I wanted her to choose adoption. I never wanted her to face the loneliness of social isolation because her peers did not have babies, or the destitution of poverty, which brings men and women to their knees in desperation forcing them to reconsider every ethical conviction. But more than anything, I wanted her to have more time to be a girl, before the tide of living whisked every opportunity away.

I also knew that only she could make the decision. It would be a dance; a dance of presenting options, and offering realities, while always affirming that it was her choice. Going to Texas was my way of saying: I love you, I will not leave you, I am your mother. I also believed that by letting go of this baby, new chances like stars would be born for both of them.

During the months of her pregnancy, I dreamed of my daughter’s second chance, the chance I had never had. In that dream, she could become Marlo Thomas in "That Girl," have her own apartment, maybe go to college and someday have a career. I would swoop in like Mary Poppins so that we could put this behind us.

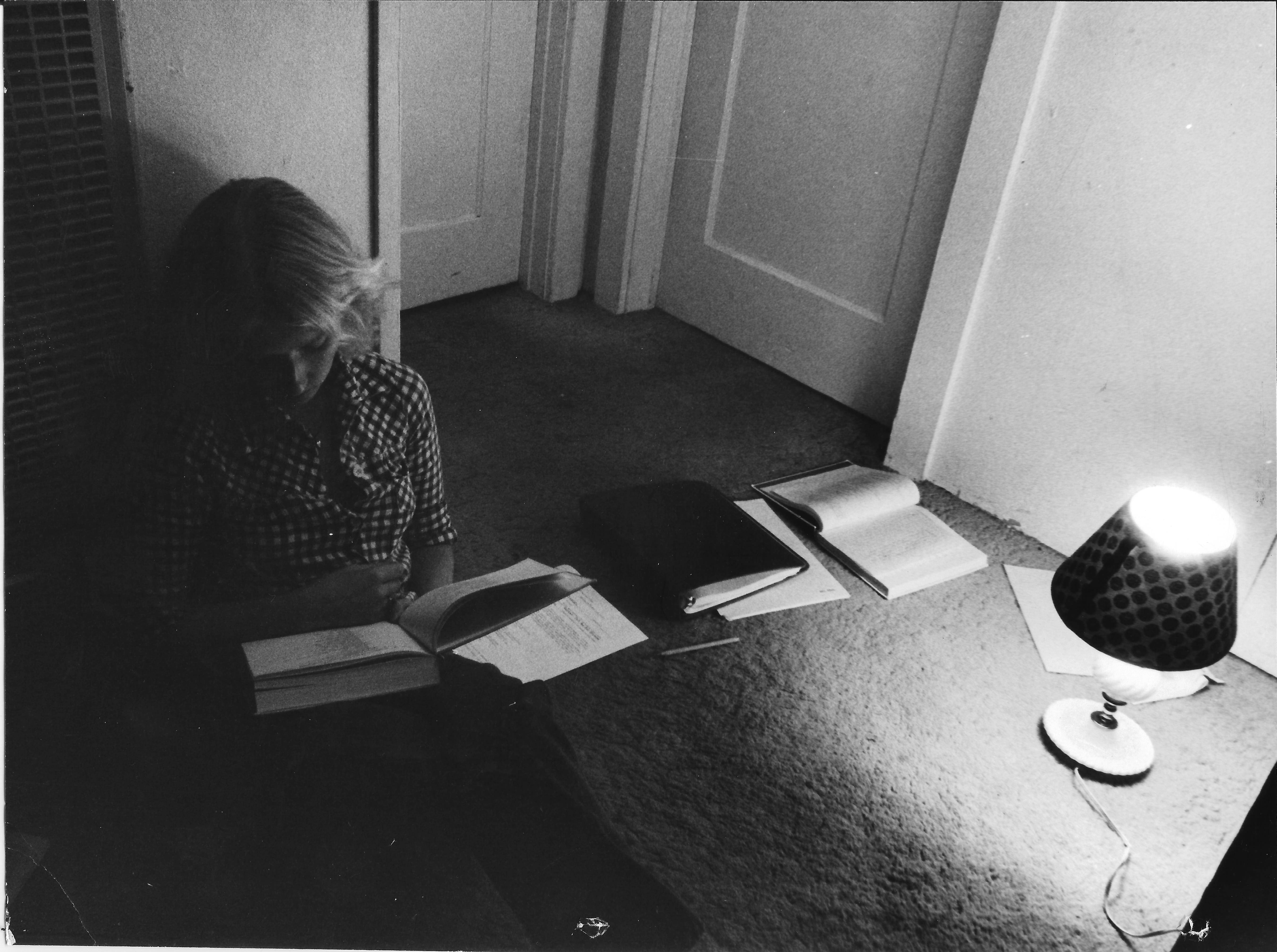

As calendar pages peeled away into oblivion, I organized, supervised and assisted her in getting information and support. I recommended books and we would read them and discuss them over the phone. I contacted my local independent adoption agency where the terms of adoption could be negotiated between the birth mother and the adoptive parents. I encouraged her to talk with them and anyone who had ever chosen adoption. She said “Yes” to every suggestion.

With months of supporting her and a turbulent airplane landing behind me, I arrived in Texas two weeks before her delivery date. Lisa and I were alone most hours of the day because her dad and stepmother were working. We spent time talking, walking, window shopping, and napping. We discussed the adoption, the parents she had chosen and the baby, but in “little steps.”

For her 16th birthday there was a family picnic at a park with lush green hills and a cooling river rolling past, its breezes caressing like a southern drawl. Surrounded by my ex-husband’s family, no one mentioned the impending delivery of a baby.

I wanted to be alone with her. She was 38 weeks pregnant and standing on the precipice of becoming a mother. “Let’s go down by the river, where it’s cooler,” I suggested.

Grabbing a patchwork blanket, we headed downhill toward the water’s edge, avoiding mounds of bee-embellished clover. We settled under the shade of a large southern tree. We sat down, and laughed out loud when we folded and tucked our legs simultaneously underneath our hips. We searched through patches of clover looking for our one lucky charm. She shifted her body in search of postures that would bring comfort from her heavy burden. Focusing on her search with her head down, and not looking at me she admitted, “I’m scared, mom, but I don’t want to use anesthesia. They say it’s not good for the baby.”

“Well honey, I’ll tell you what my grandma told me when I was 15 and pregnant – It hurts like hell but if it were that bad, there wouldn’t be so many people round here, now would there?” My daughter let go of a breath and released a cautious laugh.

“Do you think it’s a boy or a girl?” I asked.

“It’s definitely a boy,” she beamed. “Everyone says so...I’m carrying high you know.” Picking one clover over another, we explored the depths of a woman’s journey through pregnancy and birth. It was a conversation between two women, an ancient conversation. I would always remember this time with her.

“Look what I found, a four leaf clover!” I exclaimed. We both giggled. A good omen, we thought.

The Smiths flew in from California to attend the baby’s birth. They were a stable, mature, 30-something Christian couple who had tried to have children for many years. One of the reasons she had chosen them was because Mr. Smith had taken the time to sign the introduction letter himself. She thought that said a lot about him wanting to be a dad. I was touched by her affirmation of the role her dad had played in her life, and by how seriously she was considering these would-be parents.

They arrived at a time that pulsated with excitement and trepidation. Lisa was at the hospital in the early stages of labor. The Smiths were excited but cautious. They asked if I would meet them for a walk before heading to the hospital's Labor & Delivery Floor. We met on the hospital grounds, walking slowly under the shade of a tree-lined sidewalk. We spoke cautiously. I sketched out why she had come to live with her dad and the dramas that my daughter and I had survived.

“Do you think she’s taken drugs or drank alcohol?” Mr. Smith blurted out.

“I am confident she has not,” I shot back. “She has shown nothing but care and concern for this baby since the beginning.”

After that conversation, I returned to my daughter’s side, helping her ride the rhythm of labor with breath, focus and determination. She held my arm, gripping it with the unleashed power of a woman wanting to push a baby out. We did this for hours, and her stepmother, a nurse, participated to relieve me. I had no previous experience coaching a woman through birth, but this came easy. It was almost involuntary. It was primordial.

But fate dealt another blow – the baby was a girl. I don't remember the delivery. I was distancing myself in order to survive my next assignment. My first grandchild, a girl, would be forsaken by me, her grandmother. My commitment to this course seemed a whiplash of a long-ago mistake. I had handed my daughter over to her dad, and now I would support that same daughter in handing over her daughter to someone else. Stunned by this heartrending recognition, I was petrified.

My granddaughter was absolutely beautiful and perfect in every way. My daughter held tight to her, becoming the protective she-male that looked like she would kill on any suggestion of separation. The nurses said breastfeeding wasn't a good idea when choosing adoption. My daughter clung to the idea because she had read that it was best for baby. I could not pick this battle; I let it go.

My daughter sat in wonderment, her sad, stunned eyes rolling over every detail of her newborn. I could see that she was laying claim to this life. So it was no surprise when she said, “I can’t do it, Mom. I can’t let her go.” I had hoped this wouldn’t happen but the agency counselors had made us all aware that it might, especially with a mother so young.

“I’m sorry”, I told the Smiths when I called them at their hotel, “She’s changed her mind.”

There was a pause on the line and then, “We’re going home,” he said his voice shaking with anger. “Don’t call us if she changes her mind.” The next day the Smiths boarded a plane with all their baby things and no baby.

The love and admiration I felt as I watched my daughter become a mother could not belie the realities of having a baby so young, especially in Texas where any financial assistance required her to live with her parents. With my return flight to California little more than a week away, time was running out.

I remember my daughter, laying on the couch, snuggled in a cozy blanket, baby nestled to her chest, both of them quiet and content.

“Lisa, if you decide to keep her, when will you ever be able to be with her? She’ll be in daycare while you work, and then again when you go to school. How will you make it?” I asked. She didn’t respond, but tears rolled down her cheeks and on to her baby.

The next day, as she softly wept, holding her baby tight to her body, she told me that she had decided to sign the adoption papers.

I felt the urgency of it, a surge of adrenaline pulsing, beating me into action. In order to save them, I had to imbue the most profound disloyalty with the greatest love. There was no time to review the course. I immediately called the Smiths. They told me that they would adopt the baby on condition that my daughter sign the permanent placement papers before the baby arrived in California.

The adoption agency faxed the papers. Her dad, her stepmother and I sat in the front room with Lisa and her baby. There was nothing in this room to comfort me, nothing familiar or cherished. And if I were to paint the picture of this moment, everything in the room would be brown. No one spoke. I sat close to my daughter on the couch.

She wore a white shirt that buttoned down the front. Her breasts were bound tightly by a length of cloth to dry up her milk. She appeared as a hollow vessel, emptied of any fight, resistance, or complaint.

The fax machine rolled and sounded a bing summoning her dad. He left and returned with a stack of white paper. I think I read the documents: boilerplate legalese, difficult to interpret but clear this was final. There could be no turning back. “Are you sure?” I asked. Her dad and stepmother were silent.

Then as I stood at the side of my 16 year old, she lifted the ballpoint pen and did something only the strongest and best mothers can ever do. She signed the papers that would sacrifice her well-being to give her daughter a better life.

I was the only one who could take the baby back to California where her adoptive parents were waiting. No one suggested another option. My betrayal to my daughter and granddaughter would now be made physical. I would be the one to hand her over.

Boarding the plane to California with a beautiful bundle of pink, I said goodbye to my ex-husband and my teenage daughter, all of our hearts shattered and falling like confetti to the floor.

A woman sitting next to me on the plane, asked, "Is this your baby? What a beautiful baby."

“No,” I replied, “I am an adoption agency representative taking her to her new family.” Even with those treacherous words eating me alive, in my pocket I carried a talisman. It was a four leaf clover I had picked at the river’s edge the day of my daughter’s birthday.

As the plane began its descent, I silently repeated a mantra: be strong, help this child, love her by letting her go, give each of them another chance for a better life. This was the price I had to pay to prevent my dire predictions of what life would be like for my daughter and granddaughter from coming true, to prevent the rebirth of the legacy of abuse that I had ended.

“How wonderful,” she said. “New beginnings.”

* Names have been changed.

Patricia Lea Harris lives in a California Coastal town with her husband. Her writing, "Mom Marries Uncle Paul," appeared in San Luis Obispo’s New Times 55 in 2015. She is a retired community organizer and developer in women’s health and mental health. She is a Liberal Studies graduate of Shasta College. She also graduated from the Women’s Health Leadership Program at the Center for Collaborative Planning. Find her online at: www.patricialeapens.com