Streets were quiet when we left, but when we turned at the end of our block ten minutes later, a parade of parents and kids with shiny backpacks and fresh haircuts lined the sidewalk. As they bunched at our heels, their enthusiastic chatter at our backs, Riley stopped and moved to the sidewalk’s edge to let them pass. This happened over and over. If he made any comparisons about their speed versus his, he never said a thing. Still, we arrived before first bell on the first day of school.

The kindergarten classes were up a slight hill and through a gate on the right, and his classroom was the last one. Why does it have to be the last room? I wondered. All those extra steps add up. As I combed through his hair with my fingers, I felt exertion at his temples from the walk – three tenths of a mile was a long way for a little boy with half a heart who’d already undergone five open-heart surgeries. In the courtyard outside the classroom, there was a picnic table with a green umbrella, a couple of flower boxes, and a row of hooks labeled with student names.

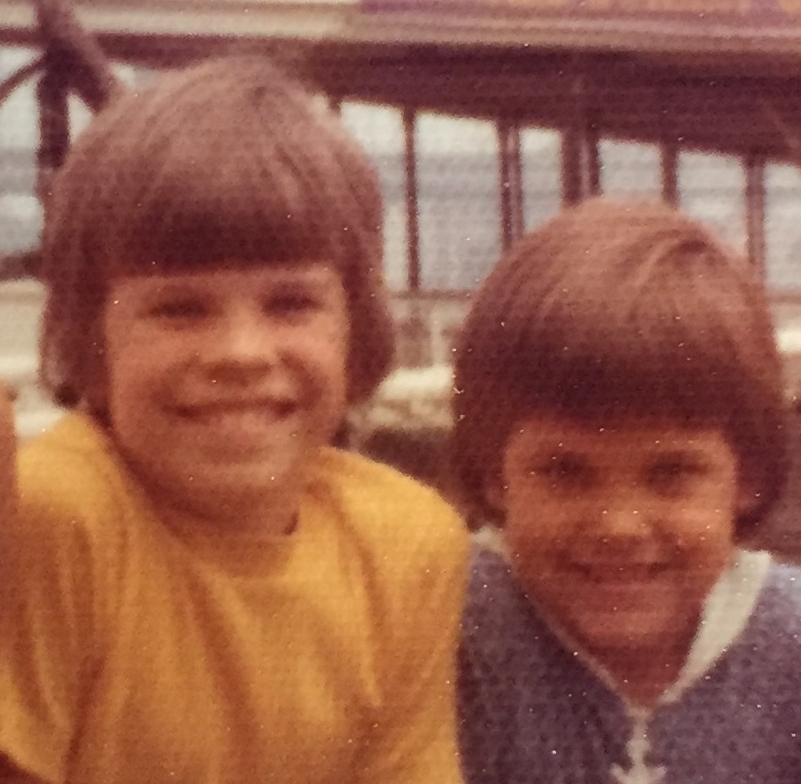

Riley found his hook and hung his backpack. “That says ‘Welcome’,” he explained to his two-year-old brother, pointing to a sign on the door. His brother wiggled to get out of the stroller. Some kids stood in a row getting their picture taken. Riley joined them, put his hands on his hips and smiled a confident grin. Flashes and clicks surrounded us and mothers in sweater sets or exercise outfits hugged their kids again and again. A ring reverberated, commemorating a small, but official step towards becoming independent little humans. Most of the kids trotted into the classroom confidently with Riley, but there were a couple of tears and hugs from kids and parents who weren’t ready to let go.

At three-and-a-half, when Riley started preschool I felt total elation. As soon as I dropped him off, I did a little happy dance and had some chocolate for breakfast. And just as I was not sad when he started preschool, I wasn’t the tiniest bit sad about kindergarten either. I was relieved, actually. This was something normal, a milestone we weren’t sure we’d ever reach given his malformed heart. It was only a year earlier that we’d met with the the director of the Pediatric Heart Failure Program at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital to talk about heart transplants.

Since then, though, Riley had not gotten worse as expected. Instead, he played a season of T-ball, learned to ride a bike, went to see a handful of San Francisco Giants games, was the topic of a San Mateo Journal cover story, and took a Make-A-Wish trip to Baltimore to see the Orioles play at Camden Yards. It included rides in limousines and side trips to see the Philadelphia Phillies and the Washington Nationals, and coincided with his starring role as a ring bearer in his auntie’s wedding.

With him starting kindergarten, I looked forward to a five-day-a-week break and some one-on-one time with his younger brother. But mostly I was excited he wasn’t in the hospital. It had been fifteen months since he was discharged from a long hospitalization that included his fourth and fifth heart surgeries. Sure, he got tired more easily than other kids, but for the most part, he would blend right in. For me, it was a relief. We’d made it this far.

I didn’t get through the school year unscathed, though, or even through the first month. One Friday evening, I took the kids to an evening concert at Burton Park with a friend. The weather was still warm. The park was packed, and the area in front of the stage was filled with kids dancing around, jumping, and riding their bikes. “Dance to the music” enticed us from our blanket and onto the blacktop to join them. Like a hula hoop, we formed a circle holding hands. It was a moment of joy punctuating the atmosphere of medical uncertainty that was as prevalent as inhaling and exhaling in our family.

Two girls came up to Riley while we swayed to the music. His eyes widened, and a smile stretched across his face as soon as he recognized them from school. He was making friends and was proud to tell me that they were in his class.

The blond girl with curls leaned over and touched Riley’s shoulder and said playfully, “Chase me, Riley.” With that command, she and the other schoolmate ran off as fast as two healthy five year olds can. He flashed a bashful smile at me. “It’s okay. Go,” I said, encouraging him to play. His little brother grabbed my empty hand, forming our new dance circle. But the song ended and the band went on break. As we walked back to the blanket, I was distracted watching Riley. His body wouldn’t cooperate. An awkward trot became a slow walk. He wanted desperately to run after them, to chase them, tag them, and continue the game. Within a few seconds, a spectrum of emotion passed through his round face – joy turned to frustration then discouragement. There was nothing I could do to help him make his body move faster.

I desperately wanted to scoop him up and tell him everything was going to be okay. But all I could do was watch him struggle and curse the rotten heart he was born with. After a minute of trying to catch them, exhaustion clamped his perfect-looking body in its claw. Like a boulder in a dust storm, he stood in the whirl of activity, disoriented by his inability to keep up. Defeat prevailed. He plunked down on the pavement, his head weighted and low.

I wiped my face, steadied my breath, and went to him. “Hey, buddy.” I kneeled down next to him and rubbed my hand in little circles around his bony back. With exasperation, he said: “I just can’t go anymore.” On the outside, he looked like the other kids, but his limitations outed him as different. He didn’t blend in as easily as I had hoped.

His words reminded me of how I had felt many times. There had been many times when I felt I couldn’t go anymore. But somehow, I just kept going. I kept finding a way to throw the blankets back and slide out of bed. I kept finding a way to drive myself to the hospital, take the elevator, push open the door to the ICU, to soothe his wounded body, to will him to get better. And I continued to find ways to get past all the what-ifs so that we could live as normally as possible. I tried not to think too much about what was to come. I just kept going. There really wasn’t a choice.

“Just rest for a bit, and when you’re ready, you can get up and try again – if you want to.” As we sat on the ground, my arms circled his warm body.

“I can’t do anything,” he said as salted tears peppered the dry pavement and his fingers pushed bits of gravel.

“Sure you can. You can do lots of things.” I tried to lighten my voice and be optimistic.

“No, I can’t,” he said to the ground.

“Hey, look at my eyes.” I lifted his chin so that his round blue eyes were facing my hazel ones. “You’re really good at math. And you can ride your bike without training wheels. And you’re really good at….”

Just then, those two girls came running to us. Their bodies looked so sturdy, energetic, unaffected by heat and exercise. I always looked at kids’ bodies and wondered how much they weighed, how much they ate, how often they threw up, how old they were when they learned to walk. I looked at the color of their lips and fingernail beds. I looked at their wrists and necks for stitch marks. I looked at the bits of skin above their collars for midline scars. I wondered if they asked to get taken to school in a stroller. Or how long they’d run before they got tired, or if they got tired.

“What’s wrong, Riley?” they asked, standing over us, pillars of youth, muscular from years of running and climbing, and a bit grimey from playground dust mixed with Indian summer heat.

He hung his head even lower so that they wouldn’t see him crying.

“He’s just taking a break,” I said. Confusion twisted their expressions before they ran off to continue their game without him. Riley and I sat on the ground for a few minutes before his brother, who I’d left on the blanket in the grass, wandered over.

“What’s wong, Wawee?” He squatted down and rubbed his big brother’s back too. After a couple of minutes, Riley wiped his face on his sleeve and was ready to get up.

“Do you want to find your friends?” I asked scanning the crowd, trying not to cry.

All I’d focused on was him being alive. Getting through this surgery and that surgery, turning three, four, five. But there was so much more that he would face than hospitalizations. There would be physical challenges and frustrations as he grew in this world. There would be his questions about why he was born this way, why his brother was born healthy. I couldn’t help but worry about how he would be treated, about how he would feel as his understanding of his own body’s limitations expanded. And while I am affected by all the experiences he will have as a result of his health problems, it is so clear now that this is his journey. My love is not a forcefield; I’m a bystander, really. A Witness. Being different and slower and more tired is a reality for him. I can’t protect him. I can’t shelter him. Nor can I filter the feelings that go along with all of that.

“No, I just want to sit with you,” he said. The three of us held hands and started walking back to our blanket.

Welcome to the eighth issue of Six Hens.