The minivan rolls into the disabled parking spot at the middle school. It is Open House, and families are invited to admire their children’s schoolwork. With my mom settled in her wheelchair, I pull evening air into my uncooperative lungs, wish I’d taken an Ativan, then cautiously push her towards the buildings. My son scampers around us. It is quiet until we go through the gate and turn toward the courtyard. Dad voices and mom voices and toddler squeals mixed with children’s laughter and a ringing school bell swarm my eardrums like a cacophony of angry bees.

Hoping most would have cleared out by the time we appeared, we arrive late on purpose. But not late enough. Tennis shoes and sweatshirts tied around waists and folders overflowing with art projects held against stomachs whiz this way and that. Basketballs bounce and swish in nearby hoops. I wish that my clothes were an invisibility cloak. Not from the familiar kids who say, “Hi, Carter’s mom.” And not from my safe people. But from conversations riddled with danger. The ones where unsafe people say unintentionally hurtful things; the ones where I’m unintentionally hurt by people who have no idea what to say and so say nothing at all. When they fail to acknowledge my other son, his image on the plaque near the lunch tables. The one that says he loved baseball and palindromes. And that he died three-and-a-half years ago.

Shoes on concrete walk families to the band room, the gymnasium, the library. Jeans and purses and basketball shorts orbit us like atoms around a nucleus. I want to close my eyes, my brain hurting from trying to understand how my two sons who were born three years and three months and two weeks apart are both in sixth grade. My sons’ dad and stepmom arrive, we say hello, their faces mirroring some of the dread I’m feeling, then it’s time to face the classrooms. With my eyes fixed on the back of my mother’s head, I turn toward the ramp that leads to the atrium. I steal a glance over the crowd. Across the yard I see a friend – a safe person. “Hi Suzanne,” she mouths, knowing being at school surrounded by families and their healthy, living children makes it hard for me to breathe. I cautiously wave and she puts her hand over her heart. I see you, I hear you, I understand that being here is painful, it says.

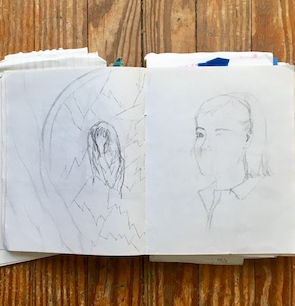

We start with English, Carter’s favorite subject. Navigating the maze of tables and chairs, my eyes scan stacks of folders and journals and poem books for my son’s name. He proudly declares his seat. His binder is green. I wonder if it was given to him or if he chose it specifically because green was his brother’s favorite color.

Sinking into his chair, I greedily absorb his yearlong efforts as I page through his binder, one assignment at a time, fully aware that the longer I’m here, the less walking around school I might need to do. “Come on, Mom,” Carter says, his thin boy arms trying to close the journal around my hand. “But you’ve written all of these stories and poems. I don’t want to miss anything.” I push strands of light brown hair away from his forehead damp with excitement before turning back to the book. “I love this one,” I say, pointing to his poem called “Gold” before starting to read it aloud: “GOLD is a mango, the sun on the sea. It is the color of a bright busy bee….”

“You can read all of it later,” he says, cutting me off, anxious for us to move on because there is still much to see and not much time to see it. I’m anxious to know if Riley is mentioned in any of Carter’s stories; I’m anxious about moving back into the hallway flowing with unknown dangers. But I follow my son and his gravitational pull.

The carpet with its calming gray and colorful swirls catches my attention. Studying it helps me avoid eye contact with other parents as we move toward his math classroom. He high fives his friends, they do a quick coordinated dance – the floss – their arms moving in unison across their bodies and around their sides as they shift their hips from left to the right.

It was only a few weeks ago that I talked with my son and stepchildren about how stressful it is to be in places where I might bump into people I know because I never know who is going to treat my broken heart with the tenderness it deserves. It deserves much tenderness because it is sore from all the beating it has done since Riley died. “Some people are safe and some people aren’t safe and I never know who is who until it’s too late,” I had tried to explain during dinner. I told them about a mom at Carter’s baseball game who had cheerfully wished me Happy Mother’s Day. I just stared at her, dumbfounded by her cluelessness. I wish I had prepared a reply, something like: “Actually, Mother’s Day is one of the most painful days of the year because the boy who made me a mom is dead.” My stepdaughter pointed out that there are probably more safe people than I think there are, if only I’d give them the chance. She’s probably right, but eyes toward the ground is the easiest way to move through the unknown.

I see Owen, Evan, Jake. They are some of Carter’s friends who come to my house. These boys to whom I offer popcorn and plates piled with veggies and dip. These boys for whom I make pizza and spray whipped cream into their mouths before topping their scoops of ice cream. They play board games with Carter; they play basketball with him. They play their instruments together. I imagine these boys color over some of the blackness created by his brother’s absence.

Horizontal pieces of cardstock adorned with colorful drawings lure me past other families to the back of the math classroom. Students had made name tags using math-tool-inspired letters. A protractor made a good capital D. A ruler made a good capital I. Each is like a riddle as we decipher the tools into letters and then into names. Admiring the math-art, I realize this was the first time I was seeing these sixth-grade projects. Studying the artwork, I find the letters in Riley’s name and imagine what he would have created had he had the opportunity. “Riley would have loved sixth grade,” I said quietly to no one in particular, thinking about his love of fonts. And math. And school.

We finish the evening in Carter’s science class. Aside from one woman, the room is empty. She wears a blue dress with short sleeves, and her bangs are pulled back into a clip. She says hello as we enter. Another mom, I imagine. My son guides us to his workstation and tells us about an experiment in which they made greenhouses out of plastic wrap and popsicle sticks, then measured the temperature inside over a period of time. “Carter, don’t forget to show them your finished greenhouse,” the woman says, pointing to a table covered in miniature see-through structures. That must be his teacher, I think. His teacher. My son’s science teacher for the last nine months…. School is done in a few weeks and I have never been in his classrooms and I have never met his teachers. I don’t even know their names.

I had completely avoided sixth grade.

Yes, I had come to school. Yes, yes. I remember. I had hung lanterns in the courtyard in October to honor the anniversary of Riley’s death. I had brought medicine to the office when my stepson had a headache. I had been to the winter band concert. I had gone to my son’s basketball games. But actual school. Classrooms. Teachers. It was all blank. Nothing. No names. No voices. No faces.

The rest of the family moves on to examine bunsen burners, but I stay put, pretending to stare intently at the greenhouses. My unconscious had done an excellent job of blocking it all. I had done the parental equivalent of putting my hands over my ears, sealing my eyes, while saying La La La La.... “Mom, come look at this,” Carter calls to me.

Not long before Riley started sixth grade, we learned that his preadolescent body needed more oxygen than his single ventricle heart could transport. We knew he would eventually need more heart surgery; we’d been given that prognosis seven years earlier while he was recovering from his fifth heart operation. We just didn’t know when. “His body will tell us,” his cardiologist said when we had asked. And the summer before sixth grade, his body spoke up. A test revealed that his lungs were trying to adapt to low oxygenation by creating faulty air sacs. It was a dangerous side-effect from which he would slowly suffocate unless something was done. That something was another heart operation.

At Back-to-School night that year, Riley’s dad and I went from class to class meeting teachers and learning about what was to come for our oldest son as he started middle school. As the Spanish teacher talked about numbers and verb conjugation and other basics the kids would learn, I marveled at the other parents, their curious expressions. They had wondered about teaching methods and homework. My mind battled bigger concerns as we stood at the back of the room near the door hoping for relief from the late summer heat. “If he has surgery in the fall, he’ll miss the winter concert,” I said quietly, leaning toward my ex-husband. “And if he has surgery in the spring, he’ll miss the spring concert.”

That October, the surgeon accomplished all of the adjustments promised, but Riley’s body rejected the new bloodflow, the different pressures. His organs shut down; his heart couldn’t manage without the machine; he died 11 days postoperatively.

“Mom, bunsen burners!” Carter calls again. A dad and his son stand near me admiring the misshapen greenhouses. Their chatter mixes with other students’ voices. The room’s shared oxygen feels inadequate to inflate my lungs, sore from all of the inhaling and exhaling they’ve done since Riley died. My mind wants to move toward my son’s voice, but the tendons and bones required are uncooperative. I look for an exit path before my eyes land on the dark floor, its pattern guiding like an airplane’s emergency lights. My limbs acquiesce, and I fumble toward the door. “I didn’t do a good job of introducing myself,” I say to the woman in blue. “I’m Carter’s mom.” She smiles and casually replies, “I know. I taught your stepdaughter a few years ago. I was her soccer coach, too.” My mind tries to organize the bits of information, to make sense of this school year, and previous years when my other children learned in these rooms. “Oh,” and “Thank you,” are all I manage before wobbling into the night.

As we roll through the courtyard, my mom asks, “Is that Riley’s plaque?” I say yes as I stop at his memorial shaped like home plate. My hand reaches to wipe cob webs from his toothy grin and from the numbers and letters arranged to summarize his short life. After a long exhale, I roll her back to the disabled parking spot, then drive her and my almost-seventh-grader back home.

Welcome to the thirteenth issue of Six Hens.